What Does (Speak) “Properly” Really Mean?

On language and body policing, narcissistic men, and the myth of Pygmalion

I was sitting across from a young family on the train a few weeks ago, a couple and their toddler son. They were sitting on a long bench seat, their stroller parked nearby. The toddler was being a toddler: moving up and down on the seat, squirming, and talking about everything happening outside the window with an impressive vocabulary. His dad asked him if he wanted a snack, the toddler said “yes”. The father took out hand sanitizer and said, “Now, sit properly, I will wash your hands and you can have a snack.” The toddler and the dad went back and forth, the boy getting distracted by something before remembering he wanted a snack, the father asking him again to extend his palms properly so he could sanitize them, and then to sit properly again so he could pass him the container with the snack. After a few minutes of witnessing these pleas for everything to be done properly, I was exhausted.

A few days later, my son and I attended a workshop about Egyptian mummies at the British Museum. The talk was being held in a small auditorium and it was mostly kids who were not in the mainstream education system meaning they likely were not used to sitting down for long periods of time and listening to someone give a presentation. There was some seat-squirming and some out-of-turn talking but nothing drastic and yet, the woman giving the presentation kept asking the children to “sit properly” and raise their hands. I have also, on many occasions, heard adults say to children “speak properly”1 or I have overheard them saying their children have picked up bad habits from other children, or even other adults like teachers, who do not “speak properly”.

I could take this essay in many different directions here. We could discuss accent/dialect discrimination, classism, linguistic discrimination, linguicism, colonialism, language policing, grammar policing, body policing, especially of adults over children. There is also the issue of correcting young children who are in fact, for typically developing children, displaying age-appropriate language development that will almost always change over time without adult intervention. (Ex. Children saying “buyed” instead of “bought” is beautiful language development as the children are typically following language patterns they have learned; “bought” will come on its own without adult intervention.)

But what I want to discuss is something slightly simpler, but with heavy undertones (or is it overtones? I just searched and it can be both!). What does “properly” really mean? As I have noted before, etymology is a funny thing as language change happens all the time so what something meant a long, long time ago, isn’t always a reliable source of information. But sometimes, it is worth looking back at how a word got its start and find meaning in its history. '

From French “propre” and specifically Old French meaning, “own, particular, fitting, exact and neat” and Latin, “proprius”, meaning “one’s own, particular to itself” (also from “pro privo” or, from the individual). The word has of course evolved into meaning something closer to “respectable and socially appropriate” but let’s focus on “one’s own”.

If properly stems from one’s own, why do we continuously try to make it mean something universal? There is something poetic in the etymology of proper, in that properly should be considered as something everyone does on their own terms, the way they want to sit, speak, squirm. Am I reaching? Perhaps. But before we ask anyone, especially a child, to do something properly, we need to ask ourselves why we consider this specific action or grammar to be proper? Is it about us or the child? Or is it about everyone else? Does this definition of properly belong to each individual or must we follow the masses? And by masses, I am not even sure who that is anymore. Perhaps cue the socio-economic discussion here because that is what it often comes down to. How, and when did we learn that something is proper versus improper? And who gets to decide?

I began writing this newsletter a few days before a friend asked me to go see Pygmalion at The Old Vic theatre. In case you’re not familiar with the George Bernard Shaw play, it was written in 1913, and is the work the 1964 film My Fair Lady with Audrey Hepburn is based on. The main character, Eliza Doolittle, is from a lower socio-economic class, selling flowers in Covent Garden when she meets Henry Higgins, a phonetics professor. Higgins along with the help of another man (!) Colonel Pickering, decides he will make Eliza his pet project and transform her from rags to riches so she can pass as a duchess in London high society. In addition to changing her language variation to what is considered posh English from her lower-class variation of English through phonetics classes, Higgins and Pickering change the way Eliza dresses, the way she moves her body, the way she eats, and essentially the way she exists in the world.

The actors in the play were amazing and although I am not a phonetician and am forever scarred after having to memorize the International Phonetic Alphabet during my MA, I was enthralled by every linguistics-themed scene! When Eliza attends an afternoon tea and uses her regular vernacular, variation and body language as opposed to the posh English Higgins has taught her, some of the other upper class attendees are amused and enthralled by this “new small talk” and “new slang” – a nice ode to language change and the desire to fit into a world through (changing) language. There are also a couple of brilliant scenes where two other women in the cast, Higgins’s mother, and his housekeeper, are both respectively astonished, disturbed, and disgusted by the sheer narcissism, ignorance, and audacity the two men possess having decided they will change this young woman’s life with no plan of what will happen to her after they are done. At one point, Higgins’s mother mutters as she leaves the stage, “Men, men, men!”

Eliza Doolittle in Pygmalion: “Well, if I was doing it proper, what was you sniggering at? Have I said anything I oughtn't?”

After I got home, another friend who was with us sent around a link about the myth of Pygmalion2. Pygmalion was a sculptor who, after deciding he was tired of all women, made an ivory statue representing his ideal woman and fell in love with his own creation. In some versions of the myth, the statue comes to life and the two live happily ever after. Higgins and Eliza do not live happily ever after and toward the end of the play, Eliza despairs that by allowing herself to be changed in the way she did, from lower class to high society, she lost the only thing that matters: her freedom. Pygmalion is about power and powerlessness, who has it, who wants it, and who will do anything to get it. It is about men and control, about recklessness and arrogance and about the ways we consider others inferior even under the guise, or perhaps especially so, that we want to save them from whatever it is we consider beneath us or often, what we ourselves fear.

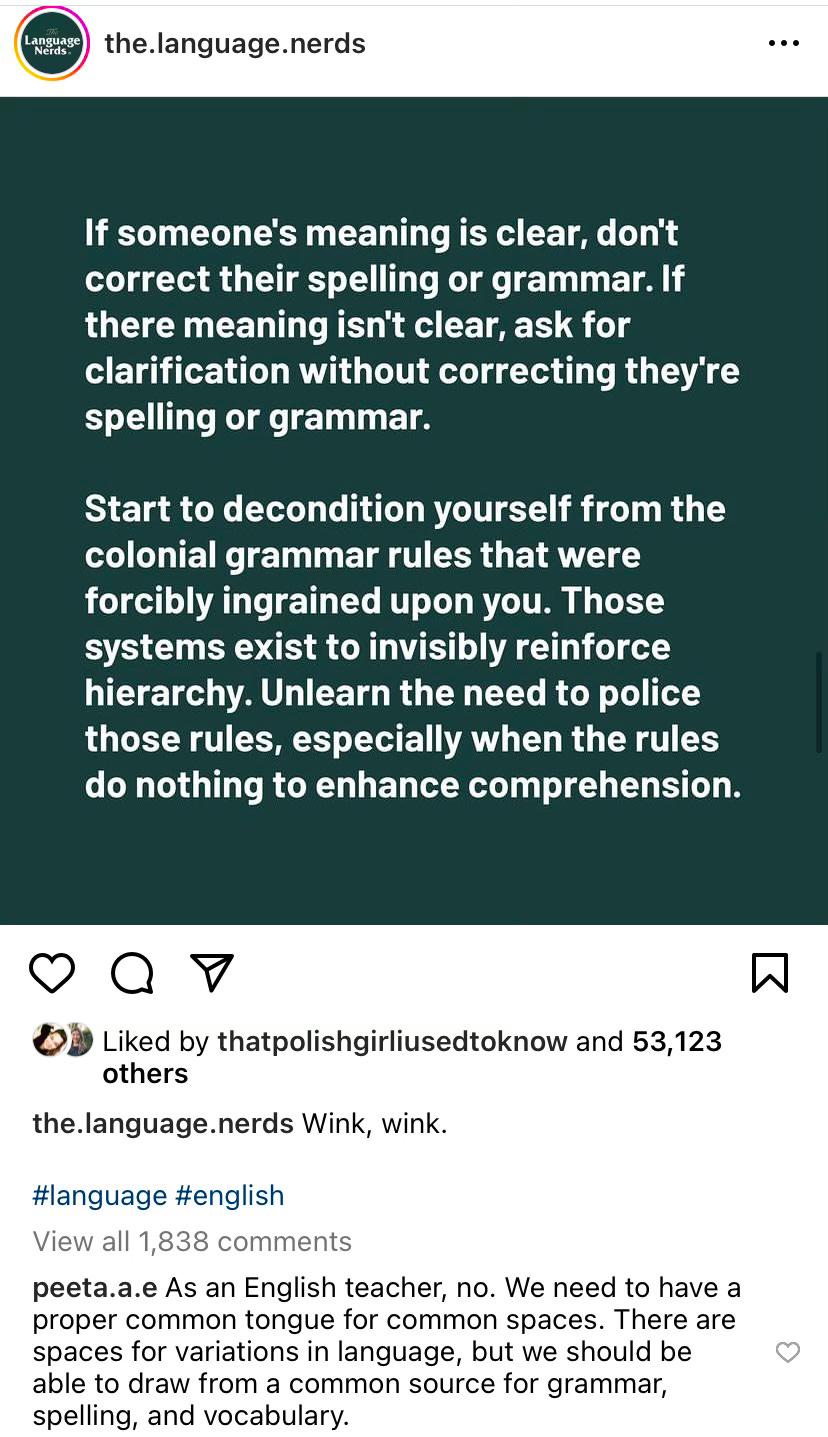

Not long ago, I reposted something from the awesome Instagram account, The Language Nerds, on a related topic. There are very few moments that are truly lost in translation because we can communicate in many ways and if we truly attempt to understand one another, that is all that matters. But the problem is we often don’t try, or we focus entirely on the wrong thing (accent, grammar, spelling).

Read the first comment on the post below. And now, ask: what is a “proper common tongue for common spaces” and what are “common spaces”? Oh, and if I am being pedantic, we have “common” one more time: “common source for grammar, spelling and vocabulary”. Does that refer to colonial grammar rules?

The only thing common in language is communication and that can be done in a multitude of different ways and in many different languages.

This is common and you’ve said this before, I get it. We are socialized from a very young age to learn certain behaviours and often we pass those on without much consideration. In the UK especially, there is a focus on the way someone sounds so again, I get it. This is not to shame anyone but to ask you to consider what “properly” means and why so many people use it, especially with children.

The Pygmalion effect is the notion that high expectations improve performance, but low expectations lead to worse outcomes (Ex. If a boss expects a lot from an employee, they will meet or exceed expectations, but if the reverse is the case and expectations are low, outcomes will also be low.)

Thank you Malwina for a human touch in an increasingly inhumane world. Beautiful thoughts and humanity in your words. As always no one is better than anyone else. Not west over east or one race over another or one class over another. What is the point of pointing out the proper and to what end? Why bother to ‘fit in’ and why would we want to anymore. Agree with you in every respect and thank you again for all your gentle reminders. Language is used to reinforce bigotry and racism and classism and ‘otherness’. Thank you for unpacking that and making it plain.