Mother is a Verb

On Sarah Knott's historical tome, artist Jenny Saville's maternal bodies & the body memory of a parent's language

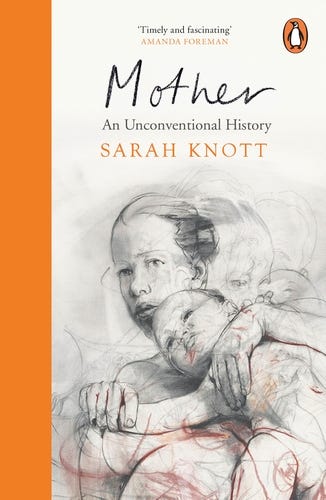

One of the early books I read about motherhood, alongside Rachel Cusk’s A Life’s Work and Adrienne Rich’s Of Woman Born, was Sarah Knott’s Mother is a Verb: An Unconventional History. (In the UK, the title was shortened to only, Mother: An Unconventional History). Knott is a historian and in the book, she beautifully details her own story of becoming a mother and mothering in those early days of parenthood alongside the stories of many other women throughout history. The book is part memoir, part historical exploration, anchored in the “tiny scenes” of motherhood, or what are considered the banal, ubiquitous and monotonous parts of mothering: feeding, bathing, birthing and so on.

Here, Knott considers the ordinary, yet if we examine how caregiving is vital to our survival as humans in fact extraordinary, actions of motherhood and mothering:

Conceiving, miscarrying, quickening, carrying, birthing. And then, cleaning, feeding, sleeping, not sleeping, providing, being interrupted, passing back and forth. These make up the visceral ongoingness, the blood and guts of being ‘with child’. The verbs.

‘Mother’ as a verb.

Side note: I keep thinking about this passing back and forth, a communal offering of care and love in life, but also in language.

I picked up Knott’s book more than a handful of years ago at a charity shop that no longer exists, not far from where I was living then in London. I was there with my two children, still both comfortably seated in their enormous double buggy/stroller. We were out for a walk, or maybe heading home after a playgroup, I am not entirely sure. I no longer remember the tiny scenes in detail that occupied my day-to-day life for so many of those early mothering years. My small children likely ate snacks, maybe fruit pouches, while I browsed the racks and shelves of the beautifully-curated charity shop — a moment of respite from caregiving for others. And then, I do remember in the back of the store on the bookshelf, an orange spine caught my eye with the cursive ‘Mother’. When I pulled the tome off the shelf, I was sold not only by Knott’s words, but by the book’s cover art.1

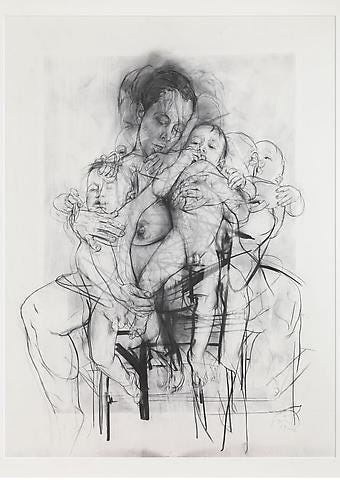

The cover image of a charcoal drawing is a close-up of a work by British artist Jenny Saville, titled, Study for Pentimenti III (sinopia). At first, it appears to be multiple characters but it is the same mother holding the same child, arms clasped around a baby arm, a child possibly attempting to wriggle out of the mother’s grasp. A mother looking outward but behind, a silhouette of the same woman looking in another direction. The artwork in its entirety is included opposite the cover page inside the book and that is where you discover the mother is pregnant , the toddler rests on the woman’s large belly, and there, appear more iterations of both the mother and the child softly revealing themselves one after another.

I bought the book and for the next few days pored over not only Knott’s words, underlining and highlighting, but also Saville’s work and everything I could find out about the artist. Saville was born in Cambridge and studied at the Glasgow School of Art where Charles Saatchi commissioned her art for his gallery. Her work on the human body is inspired by Rembrandt, Michelangelo, Titian, Matisse, Picasso and other renowned painters and artists. You can read more about her process and incredible accomplishments here. (The part about working with a plastic surgeon to observe how flesh and bodies are constructed and reconstructed was fascinating!)

Human perception of the body is so acute and knowledgeable that the smallest hint of a body can trigger recognition.

—Jenny Saville

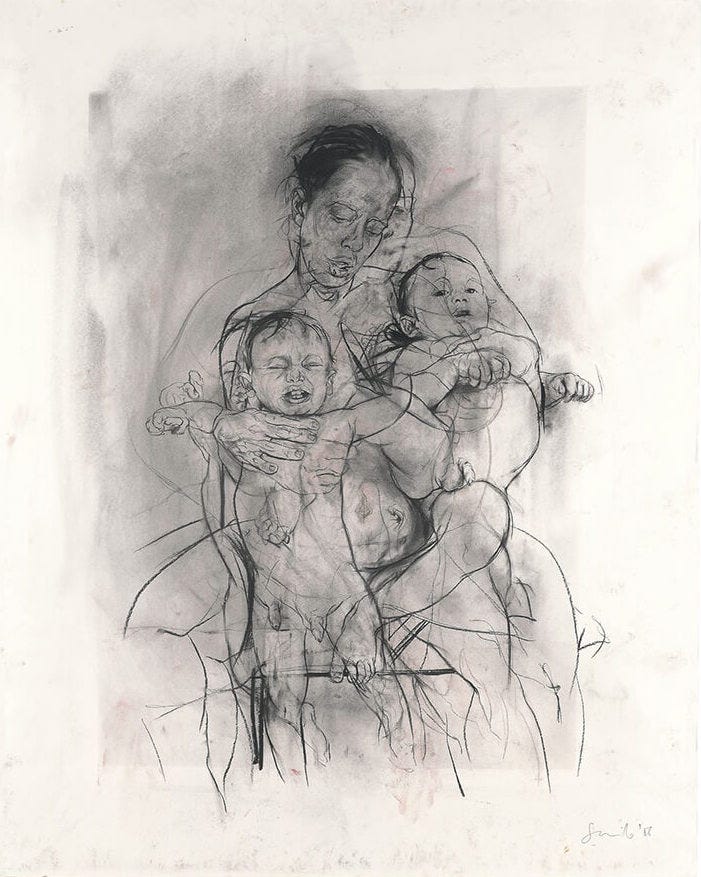

In 2007, Saville welcomed her first child and as she has noted in various interviews, motherhood had an incredible influence in her professional life. Whether it is a depiction of a mother and child, or bodies intertwined, one on top of another, Saville often depicts multiples and multitudes, line over line, hands here and there, double or triple versions of one body, each one held by another as if the subject is coming undone under the watchful eye of the self that will only let it unravel enough without falling completely apart. Apparently, Saville uses a vacuum cleaner to rub away lines to blur the distinctions between people, between bodies and parts. (I haven’t seen the connection made anywhere else, but Saville’s charcoal work is for me also reminiscent of Käthe Kollwitz’s haunting motherhood-inspired drawings. I wrote about those here.) Saville is also known for her large oil paintings and this June will have an exhibit at the National Portrait Gallery in London. I can’t wait! You can hear her chatting with

on the Great Women Artists podcast where she notes “the language” of painting many times and how it evolved and grew with her art and creative practice.In another one of my favourite books, the more linguistically-focused academic work titled, The Cultural Memory of Language, Susan Samata writes about adult subjects who do not share their parents’ first language and the effects that has on them and their families. In one part, she refers to “body memory”, or “memory sedimented in the body…day-to-day routine, interaction with familiar implements and gestures” as part of larger chapter on how she defines “cultural memory”. Saville’s charcoal drawings remind me of body memory in language, not only the repetitive nature of mothering and language, but the gestures, the physical weight, the children’s agency, the embodied language in a mother, whether she is monolingual or multilingual, but especially as she tries to, in a way, transmit (her) memories to her children, moment by moment, self by self.

I will leave you with a few more beautiful images from a 2010 exhibit of Saville’s drawings examining the mother and child. I am taking next week off here to focus on some family stuff but as always, thank you for your support however that looks like for you. If you enjoy this newsletter, let me know by liking, sharing or leaving a comment, I love hearing from you.

Thank you for reading.

In addition to a longer title, the North American edition of the book also has a different cover — not uncommon in book publishing in different parts of the world.

As always, reading your newsletter is an education! Thank you. And yes, mother is definitely a verb.

Makes me think of Mary Cassatt’s work on mothers