Her Mother’s Things & What Is Left Behind

On the cult of (intergenerational) beauty (language), how we consider our mothers, and how we judge ourselves

If you are new here, welcome and thank you so much for subscribing. And to everyone, as always, thank you for reading and supporting my work. I have been desperately trying to complete a draft of my book (!) this month, with edits coming back to me right away, so please bear with me if I am not here as much as usual. My two young children take up the rest of my waking, and often sleeping time. I promise to make it up to you very soon with some fun things planned for this newsletter. I know your time is precious so again, thank you for being here. If you have any specific language questions or want to ask me anything about raising multilingual children or mothering in multiple languages, please get in touch and I will try to answer in a future newsletter.

Beyond book writing and caregiving, the only thing my body and soul can reliably handle at the moment is art. I find solace in other people’s creations, especially in a time when the world is upside down, cruel, desperate, and in so much pain in so many places. Fun fact (maybe not), I briefly contemplated going to art school in my early twenties and used to paint (not very well) a lot. In the last newsletter, I wrote about fragments of art and writing, but also, care, and this is in a way, a continuation of that discussion focusing on motherhood objects but also, the language (fragments) of beauty ideals and ideas.

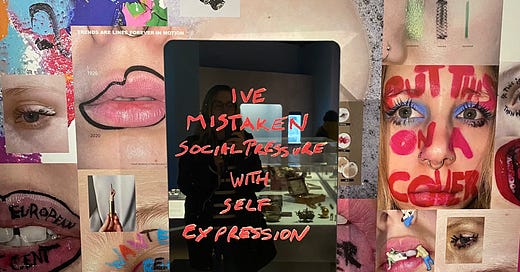

While working at the Wellcome Collection last week, I stopped by the new exhibit, The Cult of Beauty. It is an incredible show with so much work and I only saw a fraction of what was on display. But I do want to tell you about one commission, titled, “(Almost) all of my dead mother’s beautiful things” by the anonymous, always masked, artist Narcissister. In this four-part commission, the artist explores the complicated relationship with beauty passed down by her mother, Sarah Benzaquen Lumpkin.

The main part is the three-metre-tall sculpture made up of the artist’s late mother’s things: books, fabric, candles, photos, plates, a mixer, the bed her mother died in. The artist’s mother was born in Tangier, Morocco and emigrated to the United States in 1960. The daughter, Narcissister, is African/American Jewish and based in New York. In the show notes, the artist says it is her mother who inspired her to wear masks, and the work represents, “the crushing weight of beauty ideals that are passed from one generation to another” and the tension between the beauty of mothers embodied, and how children often end up deconstructing that beauty.

When I was looking at the work, I oscillated between thinking about the physical objects that get left behind when someone dies, but also, what remains of someone’s language, including body language, especially around beauty ideals, after they are gone. As I’ve written before, Polish people love to say “starość nie radość”, or, “old age is not happiness/joy” but in Polish, unfortunately, it rhymes making the anti-ageing1 message even more appealing to say. It is something I consciously never say, even when my children ask why my bones crack all the time. The last thing women, especially women, need is to feel shittier about ageing thanks to a little rhyming phrase. Are tired bones, aching muscles, perimenopause, amplified life worries about getting older joyful? No, of course not. But life is.

There are many great articles and essays on how the insecurities of parents, especially around body image and beauty ideals, are passed down from generation to generation. What I find so moving in so many of these essays is they often begin with something how, when we are children, we consider our mothers and parents to be the most beautiful and strong people in the world. There is a danger in this belief too as we are all mere humans, but there is something powerful in how children see their caregivers in a way that is often invisible to mothers themselves.

I know for many people, some of the things they heard from caregivers around beauty and bodies were hurtful and incredibly damaging. It is sometimes worth considering the context: what made someone say these things? How did their own insecurities play into these actions and verbs? And how can we do better for our own children? I am still working on trying to look in the mirror less, so my children never think they must do the same, and I had an interesting discussion with my daughter not long ago about body hair after she saw me shaving my legs. (

and write beautifully and poignantly about body and beauty ideals and how we can be better for generations to come.)But nothing changes in an instant and it takes time to undo something engrained from childhood. Considering how we embody certain ideals and ideas may begin to unravel some of those damaging stories and concepts. Language works in the same way. Just as we do not have to repeat the actions of our parents and grandparents, we can do better when it comes to language around beauty and body ideals. Before I left the exhibit, I came across a video of a L’Oréal Paris advert. Apparently, the tagline, “Because you’re worth it” has been translated into over 40 different languages. I love the multilingual take, but worth has anything to do with a company that sells beauty products.

What are some of the sayings, ideas, and ideals around beauty and ageing that have been passed down in your family? I would love to hear in the comments.

On the topic of intergenerational language & beautiful objects:

I came across this charming and moving book via the New York Times/New York Public Library Best Illustrated Children’s Books of 2023. Written by Élise Fontenaille and illustrated by Violeta Lópiz, it tells the story of a six-year-old boy who spends time with his grandfather, Luis. It is about immigration, loss, the wisdom of elders, love and of course, language. I especially love it for its title, a reference to something Luis says instead of “at the drop of a hat”. (For the longest time, I thought “when ends meet” was “when ends meat” and it referred to end pieces of meat!)

I keep meaning to go to the new art exhibit at the Foundling Museum, but every time I go there, the tokens on display haunt me for weeks to come. If you don’t know what I am talking about, the Foundling Hospital was a place in London where mothers could leave their babies if they could not take care of them for a multitude of reasons, predominantly poverty. Between the 1740s and 1760s, mothers who left their babies would often leave a small object as a means of identification like a piece of cloth, an amulet, coin or jewellery. The idea, or rather hope, was they would one day be able to return and reclaim their child. As children were renamed on admission, the tokens were supposed to be a form of identification, but that rarely happened as tokens got lost or misplaced and children never had a chance to see the tokens or the notes. You can see a selection here and read more here.

And finally, I always love

‘s “My Week in Objects (Mostly)” and found this essay by via her newsletter. It is a beautiful piece about the objects that appear and reappear around death, and what stays behind when a loved one dies.Take care of one another!

I am using the UK spelling of ageing as the American spelling, aging always makes me think of nagging and gagging for some reason. The e adds a little softness. See, I am thinking positive thoughts.

This object exhibit looks amazing! So glad to read more about it here! And agreed, the Jane Ratcliffe essay was wonderful!

Thank you for the kind words on my essay! They mean so much! And what a beautiful newsletter!