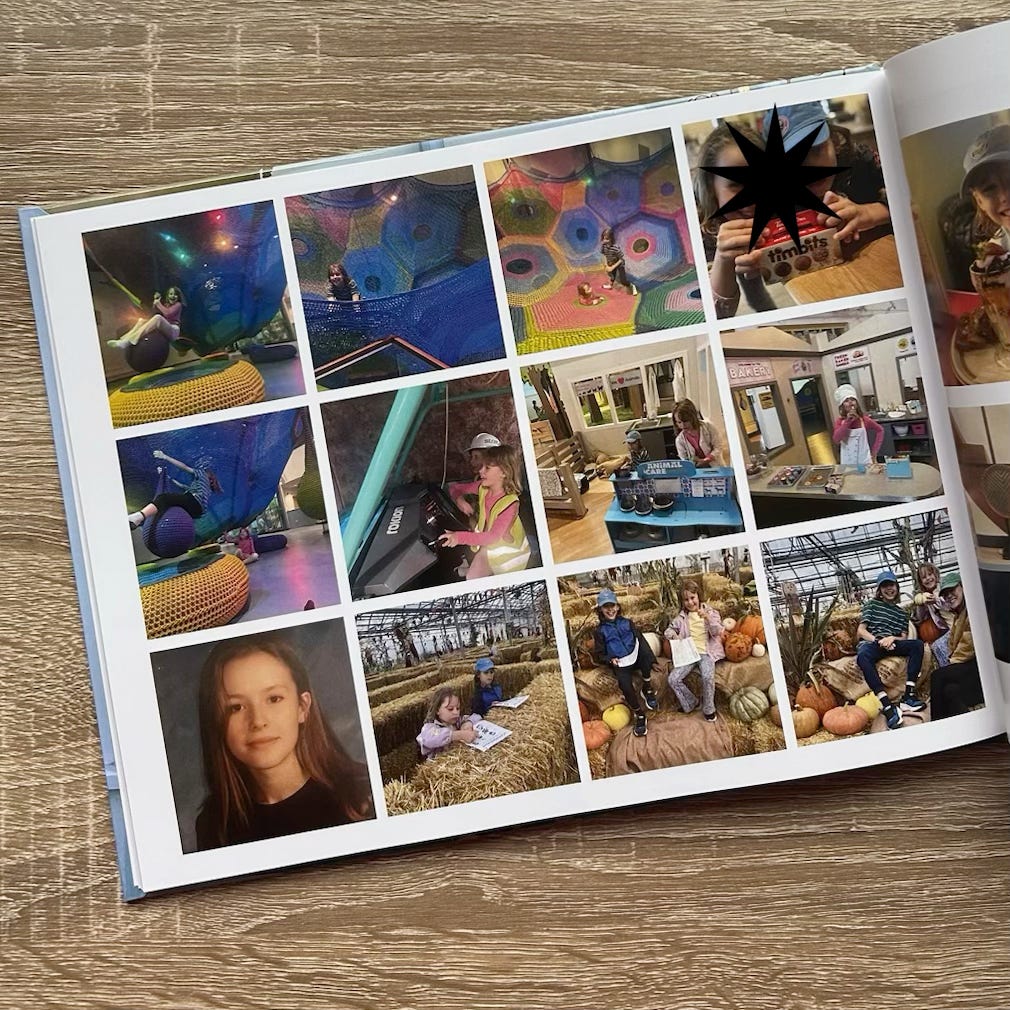

Last week, I had some photo books printed. I try to do this a couple of times a year to keep photos somewhat organised and because my children love to flip through the books. But it is not for the faint of heart.1 As I scrolled through my phone uploading photos while watching “Bad Sisters” because sometimes multitasking is the only way, and more importantly, “Bad Sisters” (!)2 I came across a school photo of my 15-year-old self. It was a photo of a photo, one I took at my mom’s house in Canada a few months ago. It is the only photo from secondary (high) school I like of myself, even now.

Sure, part of it is because my skin looks smooth and youthful, my hair is long and shiny and has yet to endure teen-girl experimentation in the form of dodgy Sun-In spray or bleach, and I am wearing a simple navy cotton tee I remember loving.3 But the other part is that I look at ease and rather calm, especially for a teenager. There is a sparkle in my eye, a sense of possibility, perhaps even contentment. Realistically, I was probably worried about something trivial that morning like not getting invited to some party or making the basketball team. I have often wished I had higher self-esteem back then and in my 20s so I know there is some romanticising here, but even so, 30 years later, I like this girl and wish we could meet (again).

I uploaded the photo to the album and it made the final photo book cut. I thought maybe my children would question its presence in the book when it arrived but they did not seem to notice. There is something poetic and powerful about including a photo of my 15-year-old self beside photos of my children on the same page, as if the old me has time-travelled to see what her future holds. Perhaps it is also a way to honour the girl I was then, the many women I have been since, and hopefully, will still become.

I am currently reading Linguaphile: A Life of Language Love by Julie Sedivy whose work I adore. Her first book, Memory Speaks was a huge inspiration for Mother Tongue Tied and I was honoured when she agreed to read an early copy of MTT earlier this year and write a blurb. In Linguaphile, Sedivy writes that her childhood was, “defined by repeated immersions in unfamiliar languages” and by five years old, due to her family’s immigration and frequent moves until settling in Montreal, Canada, Sedivy had been exposed to five languages: Czech, German, Italian, French and English.

English eventually became Sedivy’s dominant language and continued to be the main language of her adulthood. She raised her children in English and spent most of her days existing in English in Canada and the U.S. In theory, she writes, confusion around who she was, from that little girl who had five languages in her life, to the adult woman with predominantly English, should have subsided in time. But the opposite happened. It is as if an allegiance to one language obscured who Sedivy really was, leading to more confusion. She goes on to note this is not unique to multilinguals in that we are all made up of many parts, many minds, many directions and perhaps this idea of one language is simply another cover-up of the many multitudes we all carry within us.

In the beginning of her book, Sedivy writes about childhood including of course how myths around multilingual children being confused by multiple languages are still prevalent despite being debunked time and time again. Drawing on her own story of learning as a child not one, two, but five languages, her extensive experience as a linguist, but mostly her practice as an author who poetically explores language use far beyond the obvious, she comes to the following conclusion:

“Beneath the fear of linguistic confusion is, perhaps an existential terror that we do not really know we we are.”

I love this thought about language and identity in the context of multilingualism but also, more. We are all constantly trying to convince ourselves, whether it is with language or anything else in life, we are neatly-packaged entities. It makes us feel in control to “know” ourself and to create boundaries and borders, but perhaps it is a futile endeavour if we don’t consider multitudes and the plural, ourselves. (I know this is not something new, and I am sure people work on this sort of thing in therapy often, but perhaps this is simply a reminder to myself and whoever needs to hear it.) I am not saying we should not become familiar with the people we are today, and hopefully with that, find contentment, but I also think it is messy and we owe it to our past selves to sometimes glimpse back, even if it is only to acknowledge how far we have come.

Sedivy writes that this “cacophony of voices” yes, multiple languages but also multiple selves even in one language, may seem like confusion but, “what if it is really the natural state of being human?” she asks. I find it comforting, and am getting better at considering chaos as a natural state that does not have to be thought of as negative or something to fix.

I will leave you with what Sedivy writes in the conclusion of the chapter about being a polyglot, because it applies beyond multilingualism or language and really, to any part of our lives when we are desperate for control and conformity. We can embrace all of our languages and more importantly, all of our selves, even those 15-year-old teens.

“It may feel as if we have managed to keep the dangers at bay, that we have prevented inflammation of conflict by imposing strict rules and hierarchies. Nonetheless, we do host multitudes, even when we require all of them to speak the same language. The multitudes inside us must learn to reach a truce. Sometimes the negotiations need to take place in numerous tongues.”

Thank you for reading.

I say this because I want to make it clear it is a lot of work, at least for me, to upload and create a photo book. Mostly it is work I enjoy, but I also know many people, especially mothers who can’t or don’t want to do this and then feel bad about not doing something with the thousands of photos we take of our kids. I have written about this before how this is often another part of maternal labour to be the memory keeper in the family and often, mothers are left out of photos because they are the ones taking them. About the photo book, if you don’t make them, please do not feel bad, we are all doing our best. I also say it is not for the faint of heart as trips down memory lane are both heartwarming and a tad heartbreaking when you have physical proof of children growing up and time speeding along without warning or care.

Possibly my favourite show out right now, anyone want to discuss?

When I shared the photo on Instagram, a friend who I only met in my twenties, commented it was giving her Angela Chase from My-So-Called-Life vibes and honestly, that is the greatest compliment!