Women’s Words

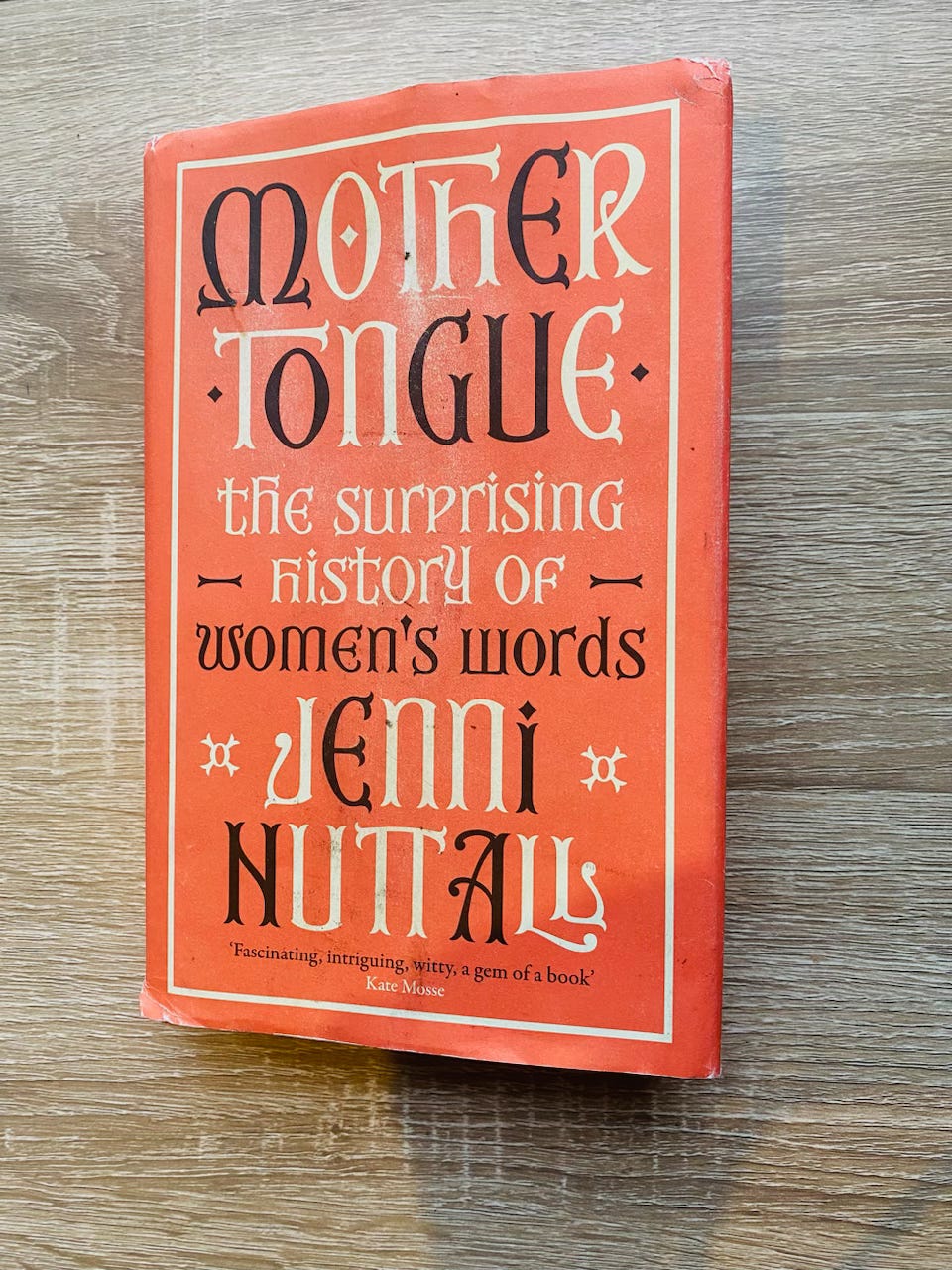

Hags & Crones! Tits & Vulvas! Cunt & Clitoris! — an ode to Jenni Nuttall’s fascinating book, "Mother Tongue: The Surprising History of Women’s Words"

She had me at Mother Tongue (obviously) and I promptly ordered Jenny Nuttall’s Mother Tongue: The Surprising History of Women’s Words when it was published last year. I have been slowly making my way through it, underlining passage after passage, shaking my head in disbelief at the suffering of women throughout time, and relishing in Nuttall’s historical prose. I connected with Nuttall on social media late last year and was so looking forward to more from her on all of this but was saddened to hear the author passed away in January after a short illness.

In her memory, an ode to Nuttall’s book that is yes, about words, but also about so much more on what it means—what it has always meant—to be a woman in a world where we are named, shamed, and forever fighting for simply the right to exist. And if any of the words in the subtitle offend you, this book is 100% without a doubt one you should read!

Divided into nine parts, from “Menstrual Language”, “Naming Male Violence” to “Words for Ages and Stages” and my favourite, “Ghyrles and Hags”, the book covers a lot of ground moving from historical writing, etymology to modern-day interpretations and uses, or sometimes, lack of (ex. many people and women still do not know the difference between a vagina and vulva). Nuttall makes it clear from the beginning, as I have often cautioned when writing about etymology, words change all the time so a word’s first meaning or etymological origins do not necessarily determine its modern-day or current meaning (a.k.a. “etymological fallacy”). And yet, it is fascinating to see how words evolve, especially “women’s words” and as Nuttall does, rediscover words that have been lost or their meanings so drastically altered.

Many of the words and terms Nuttall explores in the book are shared by transgender and non-binary people that would not classify themselves as women but, “each individual takes what they need from the common word-stock,” Nuttall writes, and “each woman must have the terms of her own choosing”, especially, “taking into account patriarchy’s habit of urging women to be quiet and of caricaturing those women who do speak up or out as gossipy, frivolous, hysterical, dull or bitchy…”

Nuttall, who was a Chaucerian scholar and lecturer in English at the University of Oxford exploring literature from the thirteenth to the sixteenth centuries, draws on her extensive historical knowledge to show us how far, and in some cases, how little, words have evolved and changed. For example, testicles and ovaries shared a single name in medieval English, “stones” because of their pebble shapes; cunt was once used in academic writing, and period was considered the less static, flux.

On the language of women and ageing, Nuttall writes:

Adjectives like mumsy, frumpy, dowdy or matronly scorn middle-aged bodies just doing what ageing bodies do. They make it sound like we’re settling into being part of the furniture, as lumpy as soft furnishings that have lost their shop-fresh bounce.

In our forties, fifties and beyond, we’re told we mustn’t let ourselves go, that peculiar turn of phrase that implies that our selves are no more nor less than our youthful appearance.

And once and for all, let’s do away with pigeonholes:

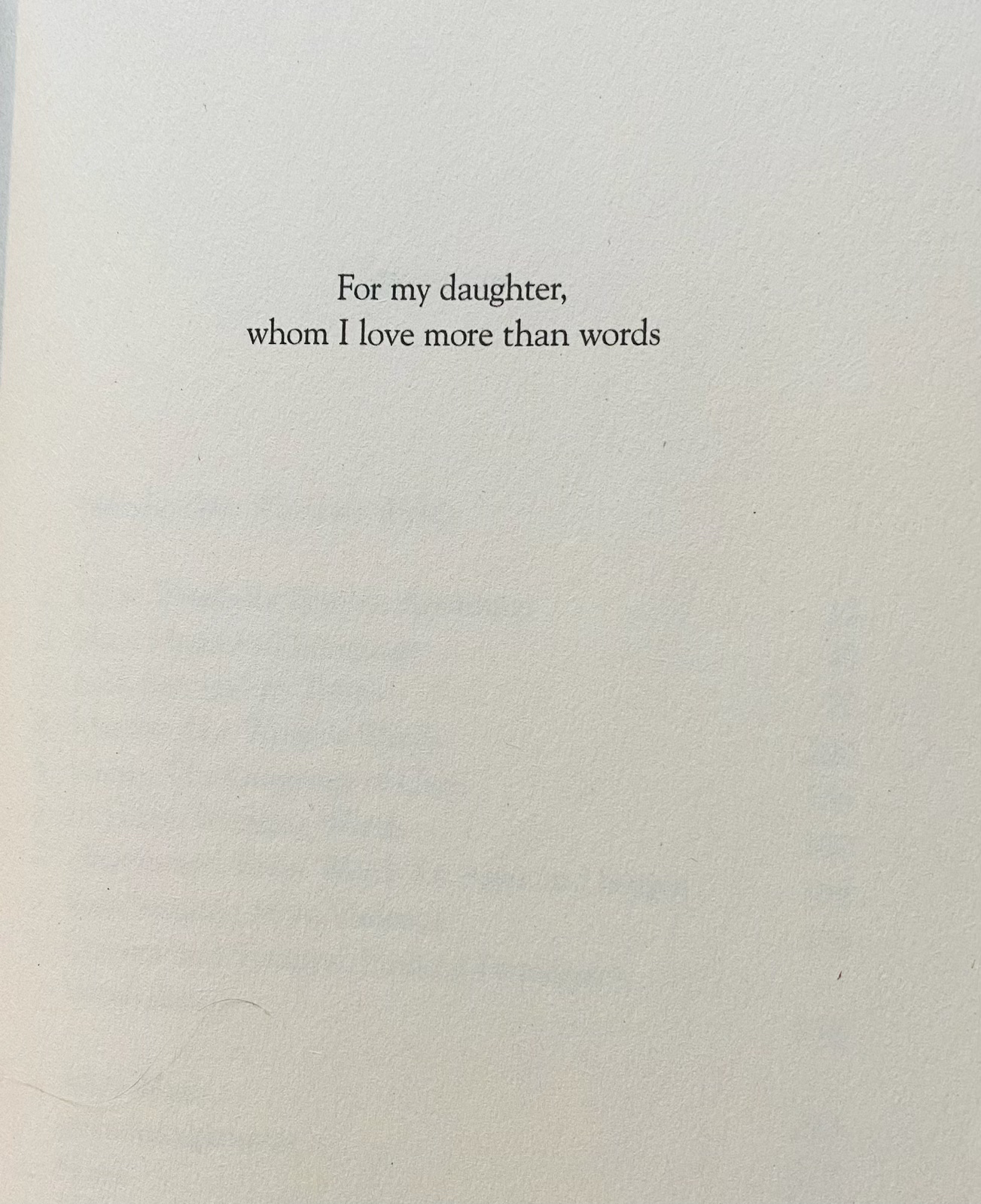

The book includes a chapter on the language of care and explores definitions, terms and notions around mothering and motherhood. But I want to end on a more personal note. When I first opened Nuttall’s book, I read, as I always do, the dedication. I have, since learning of the authors recent death, read it many more times, staring at its perfection. Nuttall dedicated the book about women’s words to her daughter, writing:

Thank you for reading and if you’re interested in more of Nuttall’s work, here is a talk she did with

And go buy the book wherever you buy your books!

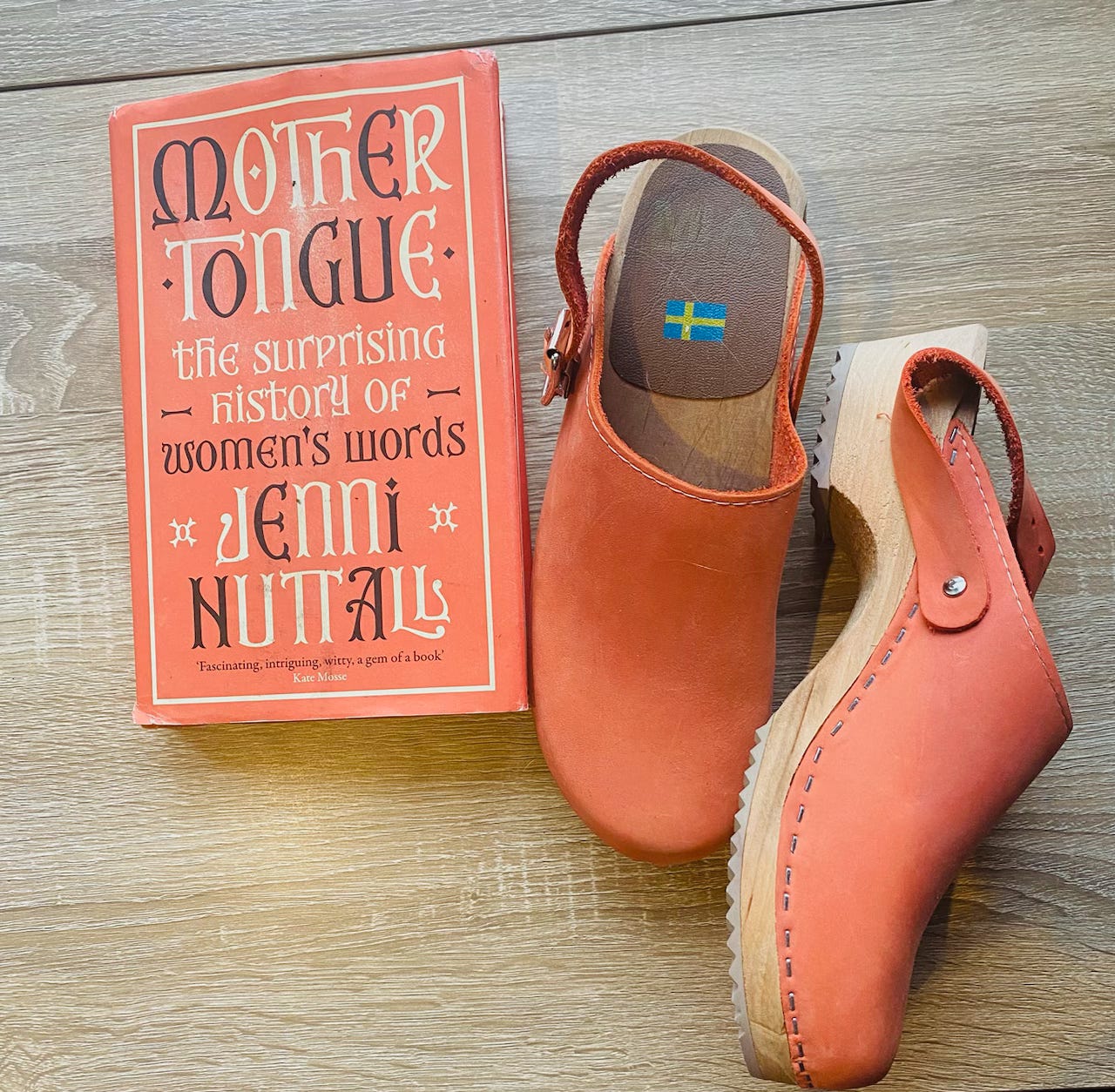

Love the matching shoes! You can be the “chic crone” wearing those 🧡