The Visual Language of Care

Q+A with the creator of the Eye Mama Project & the stories behind images from the new book, "Eye Mama: Poetic Truths of Home and Motherhood"

When I began writing this, I googled, “photography as a visual language” and ended up in a dark internet hole of fascinating, somewhat cyclical and always debatable ideas. I read, photography is not language as it is truth and therefore, not in need of interpretation (interesting) but also, unlike verbal communication, visual communication is understood by everyone (also interesting, but what about the element of individual interpretation of an image). I would love to dive deeper into this but that would take away from the focus of today’s newsletter: the new photography book, Eye Mama: Poetic Truths of Home and Motherhood.

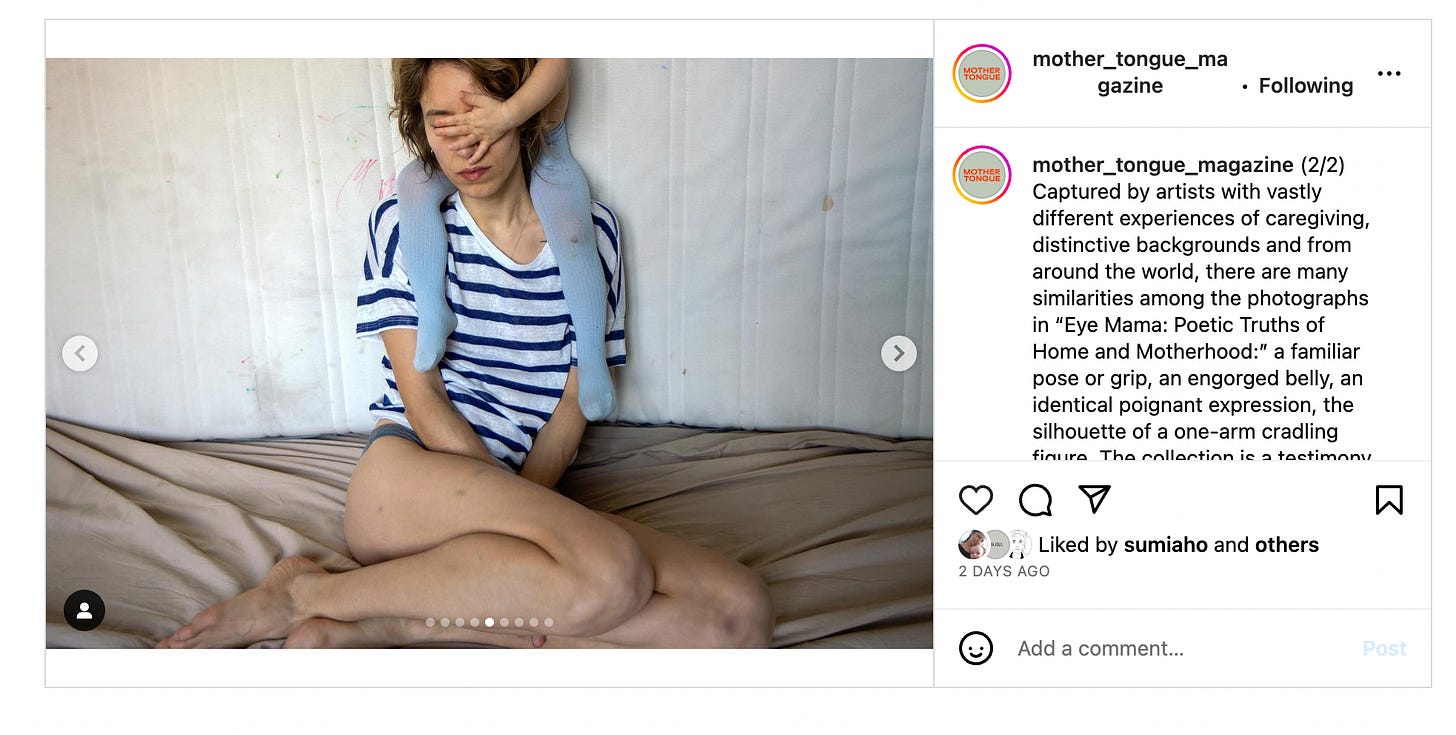

I had the pleasure of interviewing the book’s creator and the founder of the @eyemamaproject, Karni Arieli, for the wonderful, Mother Tongue magazine. You can read Part 1 here and Part 2 here.

But there was so much we couldn’t squeeze into the posts, so I am sharing more here from our Q+A, after a brief intro. I also attended the London book launch a few weeks ago where some of the photographers featured in the book, a.k.a. “eye mamas” were also in attendance and shared stories about their images. Hearing the story behind an image, what inspired the photographer, and what that moment felt like, is the best part of the language of photography. While the artists spoke, I jotted down some notes and have shared them below.

The Q+A interview has been edited for length and clarity and is part of a longer interview.

To regain a semblance of control at the height of chaos in the early days of the pandemic, Karni Arieli picked up her camera and began documenting her partner and their two sons in and around their home. Soon, Arieli, a BAFTA-nominated filmmaker, noticed other photographer mothers on social media doing the same. Arieli began sharing images on Instagram @eyemamaproject and a narrative emerged: the “mama gaze”, a look into the caregiving lives and homes of women and non-binary artists from around the world. Images like a bowl of uneaten soup with a floating plastic tiger, children’s legs intertwined with arms and more legs, engorged bellies, exhausted mothers, fresh C-section scars, and countless tender, raw and visceral moments – “the beauty within the chaos,” says Arieli.

Now, more that 200 images, from thousands of submissions, by photographers from around the world, are in, Eye Mama: Poetic Truths of Home and Motherhood, highlighting the singular yet universal narrative of caregiving rarely witnessed outside the home.

MG: I love that I'm speaking with you the day after you held the book for the first time. Tell me how that felt.

KA: It's weird! You can't fake that because all that work funnels into like a final product and it's very apparent the amount of work that you put in. Sometimes you're like, wow, all those evenings I cried. All those days, I rejoiced. All those nights I stayed up, all those days, my kids said, when is Eye Mama over so you can go back to being yourself again. My partner was like, I can't hear you talking about it anymore. Am I insane staying up in the middle of the night with no funds doing this. And does it matter? Then you hold the book. Then you are just numb, right? Because actually, it's too much. What's amazing is I just see all the stories of the mothers and the women I got to meet along the way from all these countries, and I'm really grateful for that.

MG: Why did you decide to do a book?

KA:. I wanted it to be a historical document. I didn't want it just to exist on Instagram. It's great for community; It's great for connection. I would never have gotten anywhere without it. But it's also terrible for censorship and for the instability and the fact that we got removed. I wanted something you can have on the shelf or by your bed or in the office or in the maternity ward. I want a serious portfolio in the arts, in photography, looking introspectively at what motherhood means in 2020 onwards: the beauty, the light and dark, the serious portfolio by women making beautiful work about tough content.

MG: There are two quotes in the book, one from Sally Mann, the other from Rachel Yoder’s Nightbitch. Tell me about them.

KA: Her [Yoder’s] quote really spoke to me and we debated a long time what quote to use. I knew I wanted something contemporary that set a different tone than Sally. The quote I chose in the end, it's to do with like, does it matter? Is there any point in photographing, or motherhood? Why are we doing it? Why are we spending time away from our kids documenting? Does anyone wanna see it? And my unsaid answer is yes, because here is a book about mother gaze. And this will make a difference. And this is going to be seen.

“That single, white-hot light at the center of the darkness of herself—that was the point of origin form which she birthed something new, from which all women do […]

All this to say, what should a woman fight for? Given her limited resources, limited time and energy and inspiration, what is worth fighting for? Is it art? In the grand scheme of things, it sometimes seems so pointless, even selfish. To force one’s point of view on the world—who really needs it, especially when a child needs a mother so immediately? I don’t have any answers other than that art seems essential, as essential as mothering. In order to be a self, it is essential. I should perhaps cease being a person without it. Is that enough of a reason, that it matters to me?”

- Rachel Yoder, Nightbitch

MG: Final thoughts?

KA: You can look for beauty when you look close up and you can find beauty in little tiny details, and I find it every day. And it comforts me. And I think that can really comfort you and make you see more deeply. I think seeing deeply, feeling deeply, thinking deeply.

Notes from the London book launch where some of the photographers, a.k.a. Eye Mamas, were in attendance and spoke about their images:

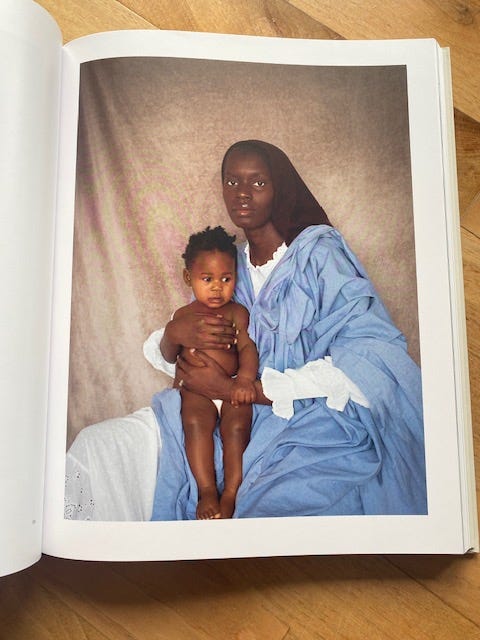

This image is of, and by, photographer Adenike Dola Posh Sogbesan with her daughter. Dola shared the story about how, when she took the image, she had severe postpartum depression and was in a very dark place. In Nigeria, where she is from, she would be surrounded by other women after giving birth, cared for, supported, enveloped by love and care, she said. But in the UK, and especially during the pandemic, she felt so alone. After sharing the image online, she heard from so many other mothers who felt the same.

Jadwiga Brontē took this image of her newborn daughter’s feet next to her C-section scar. This was Bronte’s second C-section, she told the audience at the launch, but for reasons she is not sure about (perhaps the urgency of care during COVID, trying to get patients in and out quicker, she added), the medical team used staples. This was an image Arieli had to fight for to include in the book because, she says, it was considered too real and raw.

It was incredible to hear this image by Asia Werbel is of her own daughter and her granddaughter. Werbel has a large body of work centering intergenerational motherhood with many other images of her daughter and her grandchildren. As a few of us discussed later, it is vital to see this depiction of a continuity of care across three generations, and how connected we all are.

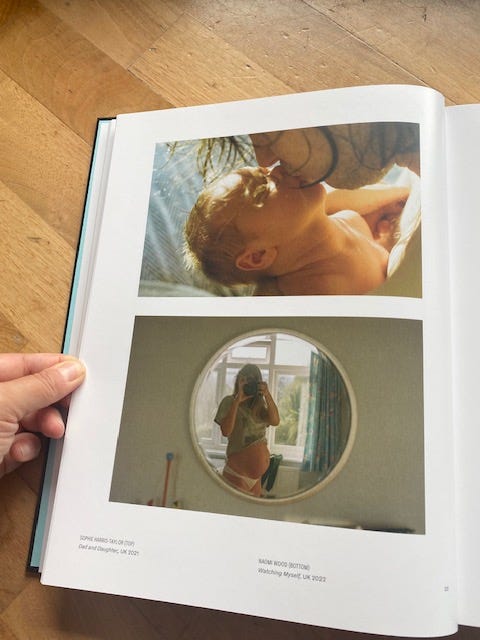

Naomi Wood and Sophie Harris Taylor, who share a page in the book were both at the London book launch and knew each other from before, they said. Wood spoke candidly about her experience as a mother of two young children. She said at times, she felt more lost while pregnant with her second child, rarely documenting the second pregnancy. And so, in this moment, she decided to take a photo of herself pregnant with her second.

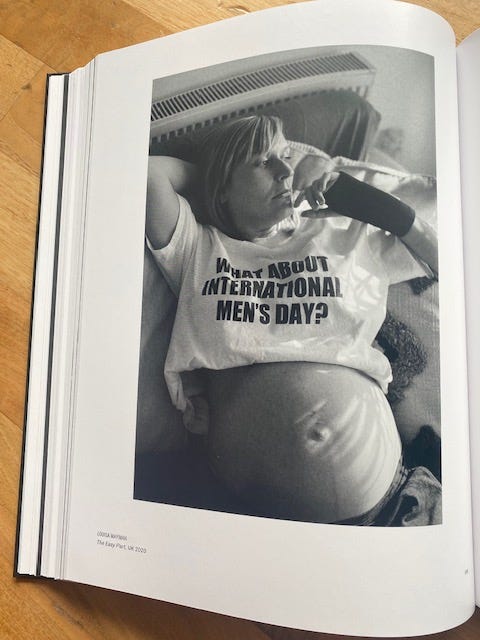

Louisa Mayman shared how vulnerable she was feeling at the time she took this image, heavily pregnant with a broken wrist. She said she grabbed her partner’s T-shirt, put it on, and took the photo. Despite the advanced pregnancy and a broken bone, the image is titled, “The Easy Part”.

I met Jessica Lindgren at the talk and she told me about this photo of her youngest son. He was obsessed with this (dead) mole and carried it around everywhere for a while, she said. There was also an overarching fascination with death itself. We also bonded over home-schooling in the UK as she home-schooled three of her four sons when the family was still living in England.

Finally, I want to mention a few more images from the book. I was so excited to see Julie Scheurweghs’s image, “Your First Home” in the book as I remember also sharing it on Instagram a few years ago. There is so much magic in considering a mother’s belly flesh in all its soft and squishy glory because it was once a home to a child.

The cover of the book is by Paula Brandão and in our interview, Arieli told me the heartbreaking story how the summer home where Brandão captured the image of her daughter’s shadow is no longer standing because of flooding in Brazil. It is a devastating testament to how fleeting a moment, and motherhood, really can be.

The image I will end on is by Katya Lesiv. The bedding in this image reminds me so much of pillowcases and duvet covers from my childhood. Look closely and you notice the child’s arm in the sleeve of the caregiver lying next to them, a brilliant tactic presumably for comfort but also perhaps so the parent has a challenging time letting go of the sleeping child when they want to sneak out. I know this so well. Lesiv is a Ukrainian artist and on her site, she writes, “Since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, I have lived through the experience of war primarily through motherhood. This is potentially a great vulnerability, but also a great strength. The feeling of presence in motherhood turned out to be a very powerful support.”

This was a great read. Thank you.