Multilingual Couples Are Sexy. Multilingual Parents Are…Tired

On love, lust & life in multiple languages & cultures, pre- and post-children

First, a few different headline ideas:

Multilingual Lovers Are Sexy. Multilingual Parenting is… Hard/Frustrating/Exhausting/Mother’s Work/Gendered Work/Often Impossible/Please Help Us (Can you tell I am writing a dissertation on the topic?) Multilingual Parents Need Therapy/Couple’s Counselling/the Fair Play Method/Really, Just A Lot More Support

But let’s start with sexy because as important as it is to talk about, discussing our collective exhaustion, in one or multiple languages, kills the mood. When I told a friend I was writing about this topic for the newsletter, she raised her eyebrows approvingly and said, “yes of course, lovers who communicate in different tongues” – her emphasis on tongues. See, sexy.

A couple of weeks ago, I linked to the article, How Multilingual Couples Express Their Love Across Languages on Instagram. It is a quick and light (my emphasis on light) read about five couples who have different first languages. Some of the couples mention the funny or affectionate things they say to one another, how they met, what language they use in which situation. But no one goes into how they interact with each other’s extended families, cultural differences that come up, and the complexity of raising children in multilingual and multicultural environments.

I should preface this entire newsletter by saying that language and love is a vast and complex area of study in linguistics, and there is a lot of brilliant research on the topic. Studies have shown that a first language is highly emotional and phrases such as I love you are more powerful in someone’s first language. However, some of the same studies as well as others, show that an LX (any consecutive language after a first one, sometimes a language that has become more dominant than a first language) can also feel emotional.

Depending on many factors, I love you might feel stronger or more emotional in a language that is not someone’s first language. There are also studies that explore how multilingualism is used in therapy, for example. Sometimes, a language that is less emotional is incredibly beneficial in therapy as a patient may be able to discuss certain topics more freely if a language does not feel as emotional to them.

The multilingual/multicultural couple that falls in love while having funny lost-in-translation moments is a common trope in film and TV. One of my favourite movies is Broken English (terrible title, great movie). Parker Posey plays Nora, who is going through some life stuff, hopelessly dating in Manhattan, feeling lost until she meets a mysterious Frenchman played by Melvil Poupaud (Julien). Nora ends up going to look for Julien in Paris because the two are young, single, free, and yes, childless. But what if they had children? Would they live in France or the U.S.? Would Julien speak French to the children and Nora English? Sorry, I am totally killing the vibe.

Remember the Before trilogy with Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke? I loved all three movies but Before Midnight was the hardest to watch. In the third and final instalment, Jesse and Céline are co-parents to twin girls and Jesse’s son from his previous marriage. If you search “which Before movie is the best?”, Before Midnight isn’t even included in the conversation on most threads.

It is sexy and romantic when two young people from different backgrounds, who have different first languages meet on a train. It is still romantic and sexy when they reunite years later, nostalgic for youth, wondering what could/should have been years earlier, even though one of them is cheating on his spouse. But sexy and romantic on vacation with young children, in middle-age, after a decade together pondering where the time and the lust disappeared to, well, it’s a different story. And of course, middle-age, family responsibilities, the glorification of youth and the short-lived excitement of early love is also all part of why the third movie feels different, for better and for worse.

Below, the closing scene of the second movie, when things were still mysterious and sexy between Jesse and Céline:

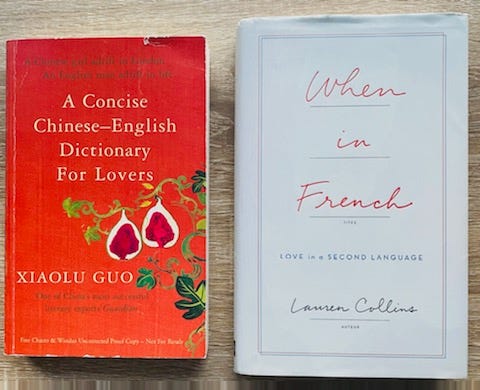

Two of my favourite memoirs about love in multiple languages are When in French: Love in a Second Language by Lauren Collins and A Concise English-Chinese Dictionary for Lovers by Xiaolu Guo. Both books do address complicated couple stuff and it’s not all lust and new love all the time. Although, Guo’s book is heavy on the lust part:

“We make love every day and every night. Morning, noon, afternoon, late afternoon, evening, early night, late night, midnight, even in the dreams…” this goes on for an entire paragraph. Try that with kids around! Both books are also about the challenges and the accomplishments of learning new languages, as both authors do, Guo, English and Collins, French.

One of my favourite lines from When in French is when Collins meets her then future French husband: “I accosted him, sticking my hand out and stating my name in a manner that I would later learn is considered, by people who are not Americans, to be fairly bizarre,” she writes. Collins and her partner do have a baby toward the end of the book and things do get a bit more complicated.

You don’t have to be a multilingual or multicultural couple to know that children, as awesome, amazing, and wonderful as they are, complicate romantic relationships and marriage. But for intermarried couples, those who have different social, ethnic, cultural and/or linguistic backgrounds, there is an added layer of complexity when children are added to the mix. Parenting challenges can be amplified when there are multiple cultures and/or multiple languages in the family, especially if one partner’s language is the societal one (the language predominantly used in the country/city of residence), and the other partner must do the physical and mental work of language transmission and maintenance of a minoritized language.

Part of my academic research on multilingual mothering includes looking at intermarried couples raising children together. Best case scenario: partners decide together how to include both cultures, multiple languages and how to work together to achieve what they both want for their children and their family. But it is never easy and often, complicated.

Tensions around language, identity and the gendered work of language are amplified in parenthood, and it can often feel like there is too much at stake to laugh at those early lost-in-translation moments shared between a new couple, when life and language felt free from responsibility, and brimming with possibility.

Some of the other scenarios I have come across in my research and other studies on language: one person feels left out if they do not speak a language that the other parent is speaking to the children; the parent who does speak another language isn’t as committed to passing it on, leaving the other partner, yes, most often the mother, to be the enforcer; the parent, yes, again, most often the mother, who takes on the language maintenance and transmission of a heritage language has to monitor, educate and ensure the family is doing enough for the children to learn a non-societal language. Language in the family is gendered work performed most often by mothers.

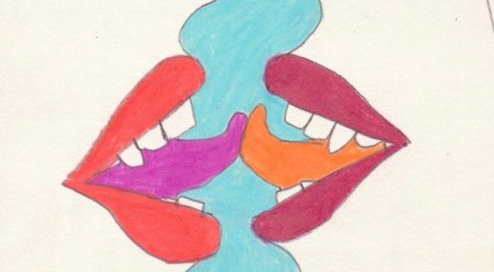

The linguistic rift between multilingual lovers is filled with desire, excitement, possibility, and sex. But once the lovers become parents, loneliness, anger, frustration, and exhaustion permeates the rupture, sometimes to the point where it overflows. Tensions around language, identity and the gendered work of language are amplified in parenthood, and it can often feel like there is too much at stake to laugh at those early lost-in-translation moments shared between a new couple, when life and language felt free from responsibility, and brimming with possibility.

The linguistic rift between multilingual lovers is filled with desire, excitement, possibility, and sex. But once the lovers become parents, loneliness, anger, frustration, and exhaustion permeates the rupture, sometimes to the point where it overflows.

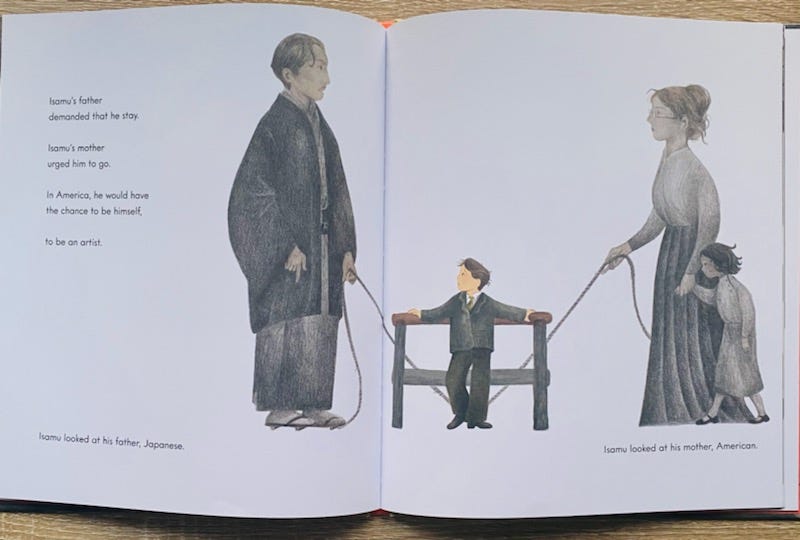

One of the most realistic images of multilingual and multicultural parenting I have ever seen is depicted in the children’s book The Snail by Emily Hughes. The story is about Japanese American designer Isamu Noguchi. His father was Japanese, and his mother was American. Noguchi was born in the U.S. but moved back to Japan as a child and then back to the U.S. when he was 14. His parents had a complicated relationship for many reasons so it wasn’t necessarily the multilingualism and multiculturalism that was the main divide in the family but Hughes’s illustration of how each parent, representing each culture, country, language stands on either side of the child, holding a rope as the child balances between them is breathtakingly accurate in how it often feels to raise children in multiple languages and cultures.

The opposing forces, one on each side of the rope, are not always the co-parents but can often also be the languages, the cultures, vying for the limited attention and time we all have. Mothers are also often the ones in the middle, teetering on a rope of the neither here nor there, this language or that one, the in-between of it all, burdened with the indecision of what to do, how to go on. I feel this so deeply, so often. At times, there is a feeling of indescribable defeat while the next moment, an undeniable will to go on, to keep moving forward.

I don’t want to end on a sombre note but sometimes, it is the only way to remind ourselves that hard things need to be discussed. But I do promise that multilingual parenting, like any parenting, can be the most joyous, amazing, and extraordinary experience in life. I say this from my own experience raising bilingual children but also from hearing so many other stories.

As always, thank you for reading.

A few more related & sort-of related things:

February 21st, was Mother Language Day, an incredible initiative to celebrate linguistic and cultural diversity around the world and to ensure everyone has access to education in their first language. (I don’t use “mother tongue/language” or “native language” as a synonym for a first language and instead, us L1 or first language as the other terms are loaded, complicated (when mother is taken literally) and discriminatory in the case of native. Also, many people have multiple first languages. The initiative is amazing and necessary, but just a reminder:

Happy Mother Lang Day! Annual PSA from your friendly neighbourhood linguist: "mother" in mother lang (tongue) too often makes mothers raising bilingual kids feel it is their sole responsibility, leading to feelings of frustration & guilt. All mothers & families deserve support.More than 6,700 languages are spoken worldwide but at least 40% are threatened with extinction. The classroom has a vital role to play in keeping them alive! @UNESCO is calling on countries to implement mother language-based education: https://t.co/8IndXt4Tsx #MotherLanguageDay https://t.co/DvBEYzZZzl

Happy Mother Lang Day! Annual PSA from your friendly neighbourhood linguist: "mother" in mother lang (tongue) too often makes mothers raising bilingual kids feel it is their sole responsibility, leading to feelings of frustration & guilt. All mothers & families deserve support.More than 6,700 languages are spoken worldwide but at least 40% are threatened with extinction. The classroom has a vital role to play in keeping them alive! @UNESCO is calling on countries to implement mother language-based education: https://t.co/8IndXt4Tsx #MotherLanguageDay https://t.co/DvBEYzZZzl UNESCO 🏛️ #Education #Sciences #Culture 🇺🇳 @UNESCO

UNESCO 🏛️ #Education #Sciences #Culture 🇺🇳 @UNESCOOn the topic of love, I saw this via Cup of Jo: a “visual exploration and celebration of love in the Middle East and North Africa”

Also, on images of love, I can’t wait for the Eye Mama book, on the narratives of mothering and home, and will write more about it soon but you can pre-order now.

And finally, this by Aubrey Hirsch on maiden names (hate that term so much!) She wrote this article last year about her kids having her last name and I commented how one of the biggest regrets I have is not adding my last name to my partner’s last name when naming our children. It is a bit more complicated for me as my last name is the feminine version, so when our son was born, I didn’t think it made sense. And now, I think about that decision often. More to come soon.