Happy new year! Thank you so much for being here old and new followers, and I hope this year brings us many wonderful conversations about language, multilingualism, mothering and much more. I’ve had a slow start to the year for different reasons, great ones (we were away visiting friends and family) but also, frustrating (relentless winter viruses in our home) so I am going slowly into the new year. If you need the same, I hope you too are taking it easy in this strange month.

If you follow me on Instagram, you may have seen I was in Kraków for a few days with my partner and children right after Christmas. As a short recap because it is relevant to this essay, I was born in Kraków and lived there until I was four years old before we immigrated to Canada via Sweden. After the fall of communism, we would make almost yearly summer trips back to Poland with my parents where we would see our extended families. Many of our family friends in Canada were also Polish immigrants as there was a big immigrant community in my hometown at the time with families trying to pass on the Polish culture and language to their children who were growing up as Polish-Canadian. I write more about this in Mother Tongue Tied and what that duality of here and there, two linguistic and cultural identities, meant to me, especially after having my own children.

This four-day trip was predominantly to see one of my oldest and dearest friends who had a very similar upbringing to my own as a child of Polish immigrants in Canada, and who was going to be in Kraków at the same time with her partner and children. As I am based in Europe and she is in North America, we rarely get to hang out so this was the perfect excuse to meet in Poland. The last time we were in our birth cities together, we were around the same age our children are now, living our childhood and adolescence between the here of Canada and the there of Poland.

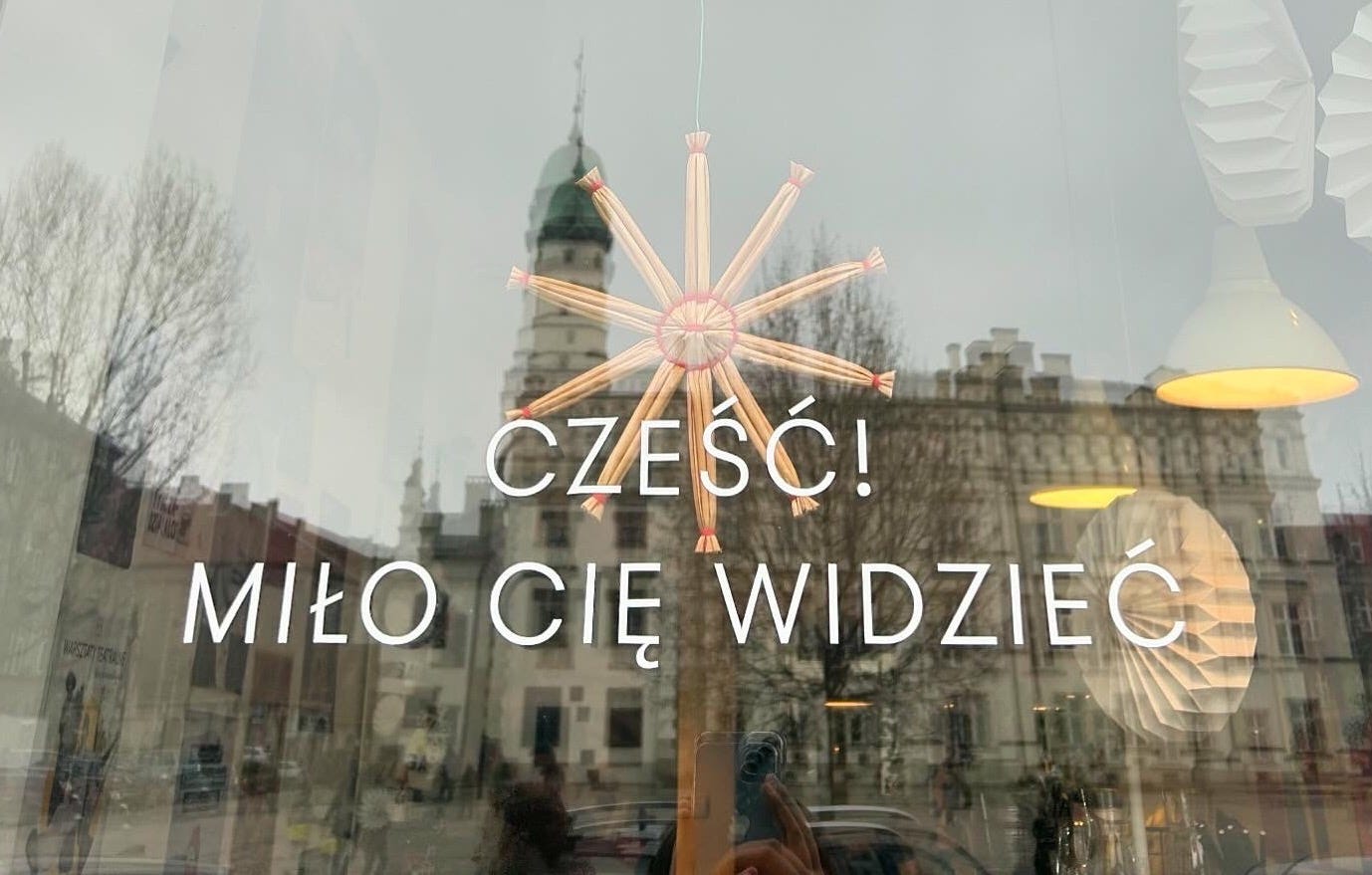

I’ve written about the linguistic landscape of Kraków before, about its graffiti that feels very much old and new, the soundscape of Ukrainian on the streets, the street art and business names that are ironic, charming or both. Notably this time around, I was told to check out a cafe called Cytat (translation: Quote/Quotation) that is filled with bookshelves and stacks of books and where the staff give out little paper quotes from books with every coffee. I mean come on, that is so charming.

On this trip, I also learnt about a store called “Pan tu nie stał” (translation: You were not standing there/here, sir). It is a nod to the Communist era when people would stand in line for goods and food, sometimes all through the night, my mom reminded me the other day when I told her about it. These were desperate times, few of us from my generation can even imagine, and unsurprisingly out of desperation, lack of time, greed and likely utmost frustration at what was happening, people would cut in line and that’s where the slogan comes from. Unfortunately, the shop was closed when we tried to go but through the window and from what I hear, it too is a charming spot filled with kitschy clothing, home accessories and paper goods. Originally a blog by the same name, launched by a sociologist and graphic designer who were inspired by vintage Polish designs, the idea morphed into a store and then two more in different Polish cities.

The communist slogan got me thinking about memory and language or how we pass on sayings or slogans that have a profoundly different meaning from generation to generation. I asked my mom, who remembers the line-ups, the desperation and the to-me-surreal events of that time in Eastern Europe, if the slogan evokes any emotion, good or bad. I was mostly wondering, I told her, if people who lived through this would feel as if having a shop with this name is an ode to a time we should never forget, or a somewhat laissez-faire and in turn potentially offensive take on something that unless you experienced first-hand could never comprehend.

But that is the thing with memory and language, the moment an event happens or something is uttered, it is gone and done and hindsight changes everything. What feels acute in the moment can soften over time, fade or in some cases, grow and evolve into something debilitating. How does the weight of a phrase change over 40 years? This can of course apply to anything said in the past. As my mom and I talked about our immigration, we also talked about how you can never predict what will happen, in general obviously, but specifically in our conversation about a country in crisis and how it can get better with a social movement and a change of government, or sometimes sadly, also get worse. When things get “better”, does the meaning of a in-the-moment slogan like “You were not standing here/there, sir” become figurative and in turn, without the weight of the original meaning? Or, is it the opposite and should the next generation ensure its literal translation lives on to never forget the desperation and how bad it once was? The answer will depend on the generation, on the person, on the context. But then again, I think another slogan/saying is relevant here: “The more things change, the more they stay the same.” (Or maybe even, “History repeats itself.”) Take that as you will. (Maybe I should start my own quote cafe ha!)

I have started to sift through my PhD data again. I took some time off from my academic commitments to write my book and then to deal with some personal stuff. It has been a while since I read the interviews I conducted with mothers around the world about raising multilingual children. One of the themes that comes up in the data is the mothers’ childhoods. Many of us, multilingual or monolingual, want to recreate parts of our own childhoods for our children. In multilingual families, it is often language and culture that is at the forefront of those desires.

This trip to Poland was the first one since my father died.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Motherlingual to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.