Language as a Home, Mother as a Bridge

And why not add noses, fences, houses and life and death to the mix!

I recently saw '1880 THAT', a new exhibit at the Wellcome Collection in London by Christine Sun Kim and Thomas Mader. The show is about language as a home: an essential place of belonging, and explores what it means to live with the threat of losing one’s language.

The title refers to the Second International Congress on Education of the Death, held in Milan in 1880. “THAT” is “an emphatic expression in American Sign Language, which adds weight and significance to a preceding statement.” While reading about the exhibit, it was the first time I learnt that at the 1880 conference, Alexander Graham Bell was a staunch supporter of the oral system, to the point he worked and fiercely advocated to replace sign language in Deaf schools in favour of speech and oral education. This meant Deaf children were to be taught to communicate through lip reading and speech instead of sign, effectively losing the only language they knew. A truly cruel act. After the conference, teaching of sign language was suppressed and the result was the exclusion and stigma of Deaf people. People that were already excluded and stigmatised at the time, and now they were also losing their language, their linguistic home.

As the show’s programme outlines, the majority of the conference attendees, a conference about the education of the Deaf (!), were hearing people. And the effects from that meeting were devastating and consequential for years and years to come, a subject Kim and Mader tackle brilliantly and playfully in their work. I learnt so much.

Language is multimodal and there are hundreds of different sign languages around the world. I write about this a bit in MTT but the main message I wanted to get across there is that if Deaf babies do not have access to sign language, that is language deprivation. One of my favourite things I learnt while researching the book is that babies whose mothers use sign language are exposed in utero to a similar sing-song rhythmic movement of their mother’s hands just like hearing children are exposed to their mother’s voice.

My favourite piece in the exhibit is “Look Up My Nose” a giant sculpture based on the noses of Alexander Graham Bell and his father. Both men had a disdain for sign language and the sculpture is also a play-on the saying “look down your nose” when someone feels superior. It also references how the nose plays a pivotal role in sign language and can convey grammar, nuanced expression and vocabulary. A number of other works explore body language and facial expressions in sign, and especially, the vulnerability of the idea of language as a safe space and a home and what it feels like when that is under attack — a message that is echoed for users of many endangered or stolen spoken languages as well.

As you read this, I am getting ready to go to Canada where I will be presenting a paper on motherhood and multilingualism at a linguistics conference. As I worked on the presentation the past week, the writer in me wanted something poetic to end on. As an academic, I had to consider my findings obviously, but as a writer who thrives on coincidences and metaphors, I wanted somewhere soft to land. In one of the papers I cite, the authors note how maintaining a heritage language is often owed to dedicated mothers (true) who are the bridges between homelands, grandparents, their own children, and I will add, all while maintaining their own identities, aspirations and emotions. I don’t think it is unique to multilingualism either. Mothers embody acts of care as a bridge from here to there, in all elements of mothering. Language is part of that.

At the conference, I will end my presentation by mentioning the bridge reference, but I have also thrown in some fences, as cited from another paper where the author writes how when a language is lost in the family, it can create a barrier not only between the mother’s past and present but also, as a symbol of an emotional distance between mother and child. Bridges, fences and yes, homes — truly a poetics of space. (My ode to Louise Bourgeois’s Femme Maison/Woman House from a couple of years ago.)

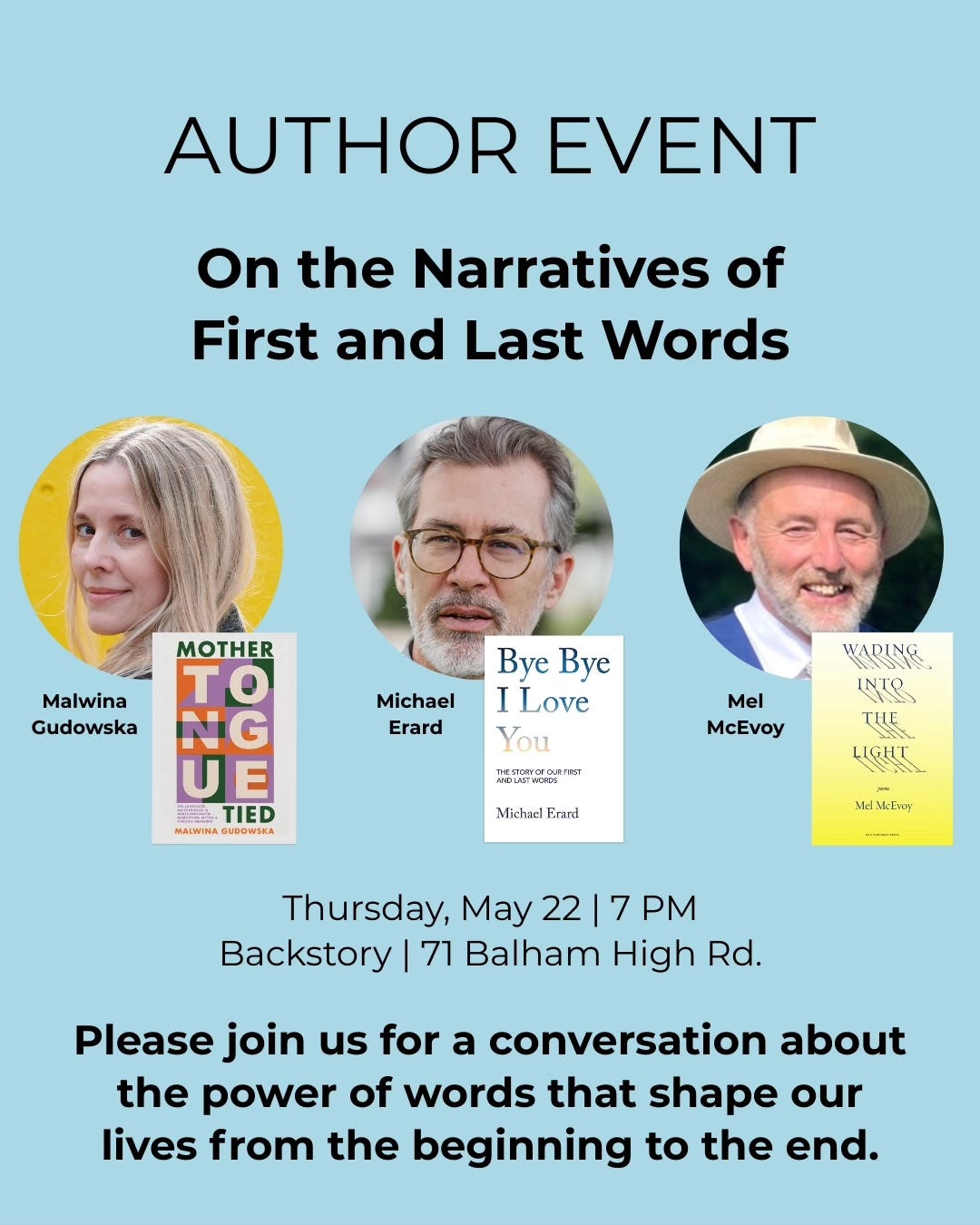

I look forward to reporting back on the conference soon. And lastly, if you are in London or nearby, I will be at bookshop in Balham on May 22nd, at 7 p.m. for what I think will be a brilliant conversation with two other authors. I will write more about both of their books next week and what we hope to discuss, but putting this out there today in case you are free and want to join. We hope to hear your stories of first and last words, and the power of language in the beginning and end of life. I would love to see you. If you can’t make it, feel free to share your stories in the comments.