The last time I posted about Sabrina Orah Mark’s writing, my son had just celebrated a birthday. I quoted a passage from Rapunzel, Draft One Thousand, from her column in The Paris Review on fairy tales and motherhood. The idea of birthmarks (also, birth-marks) and longings was exceptionally raw and heavy for me at the time, as it seemed more and more obvious my son was moving further away from young childhood. We were also mourning the death of a tiny pet and I kept thinking about the spiral of our days and my inability to take hold, grasp them in my hands, and will them to pause, just for a moment so I could catch my breath.

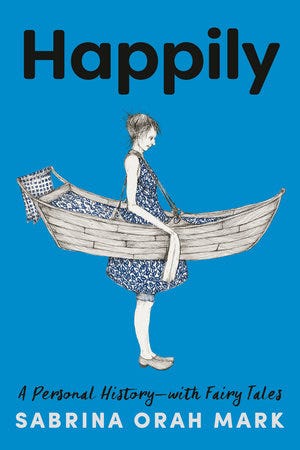

As I write about Orah Mark’s work again, this time about her new book, Happily: A Personal History-With Fairy Tales, my daughter has just this week, also celebrated her birthday. Every year, with every birthday my son and daughter celebrate I think to myself, this feels different, this feels so much older. Of course, every year, it is true because it is different, it is older.

Happily is a collection of 26 essays (plus a prologue and an epilogue) about Orah Mark’s life as a mother, stepmother, daughter, stepdaughter, wife, lover, sister, and writer, each one enveloped and infused by one, or multiple fairy tales. Reality and fantasy intertwine, simultaneously threatening and illuminating the writer’s life. As a Jewish woman raising Black boys in the American South, Orah Mark explores what it is to live and mother in times of political upheaval, racism, a pandemic, while also examining the mundane every-day stuff of parenting and life, all with incredible tenderness and magical insight. I had read most of the essays before in The Paris Review, but there was something whole or rather, holy about having all the tales in one tome, together, one after another. Orah Mark writes:

“Like stretches of ancient roads, I connect pieces of fairy tales to walk me through motherhood, and marriage, and America, and weather, and loneliness, and failure, and inheritance, and love. I keep trying to use the words that might appear on the page I am looking for.”

The most tender moments in the book are, not surprisingly, the ones she shares with her two young sons.

“If not for you,” says my son Eli, “I’d be nowhere.” “If not for you,” I say, “I’d be nowhere, too.”

I also adored the many brief appearances Orah Mark’s mother makes throughout the book, usually swearing and trying to pull her daughter out of fairy-tale fantasy and back into her don’t-give-a-fuck reality.

“Fuck the bread,” says my mother. “The bread is over,” writes Orah Mark in the essay she first published in May 2020 in the early days of the pandemic and bread mania.

The language of fairy tales is not so different from the language of lullabies. It is repetitive and rhythmic, simple and short, and was born out of oral tradition. There is good and evil, conflict and resolution, a moral lesson and plenty of magic, fantasy, and whimsy. Fairy tales do not differ much between languages and cultures although, there are ones that are much more gruesome and darker than others, and many versions of the same story. You can read more about the language and history of fairy tales here, here and here and about The Fairytale language of the Brothers Grimm.

I used to think fairy tales were simply a form of childish distraction, so far from the truth we could not possibly relate. But after reading Orah Mark, I realized these stories are created from our likeness, a musing on something hidden deep inside all of us, familiar rather than fantastical.

“We turn to fairy tales not to escape but to go deeper into a terrain we’ve inherited, the vast and muddy terrain of the human psyche. Fairy tales, like glass coffins, like magic mirrors, give transparency to the reflection of the human gaze. Fairy tales are homemade stories turned inside out. You can see the threads, the stitching line, the seams. Sometimes a needle is still attached to a loose thread, hanging.”

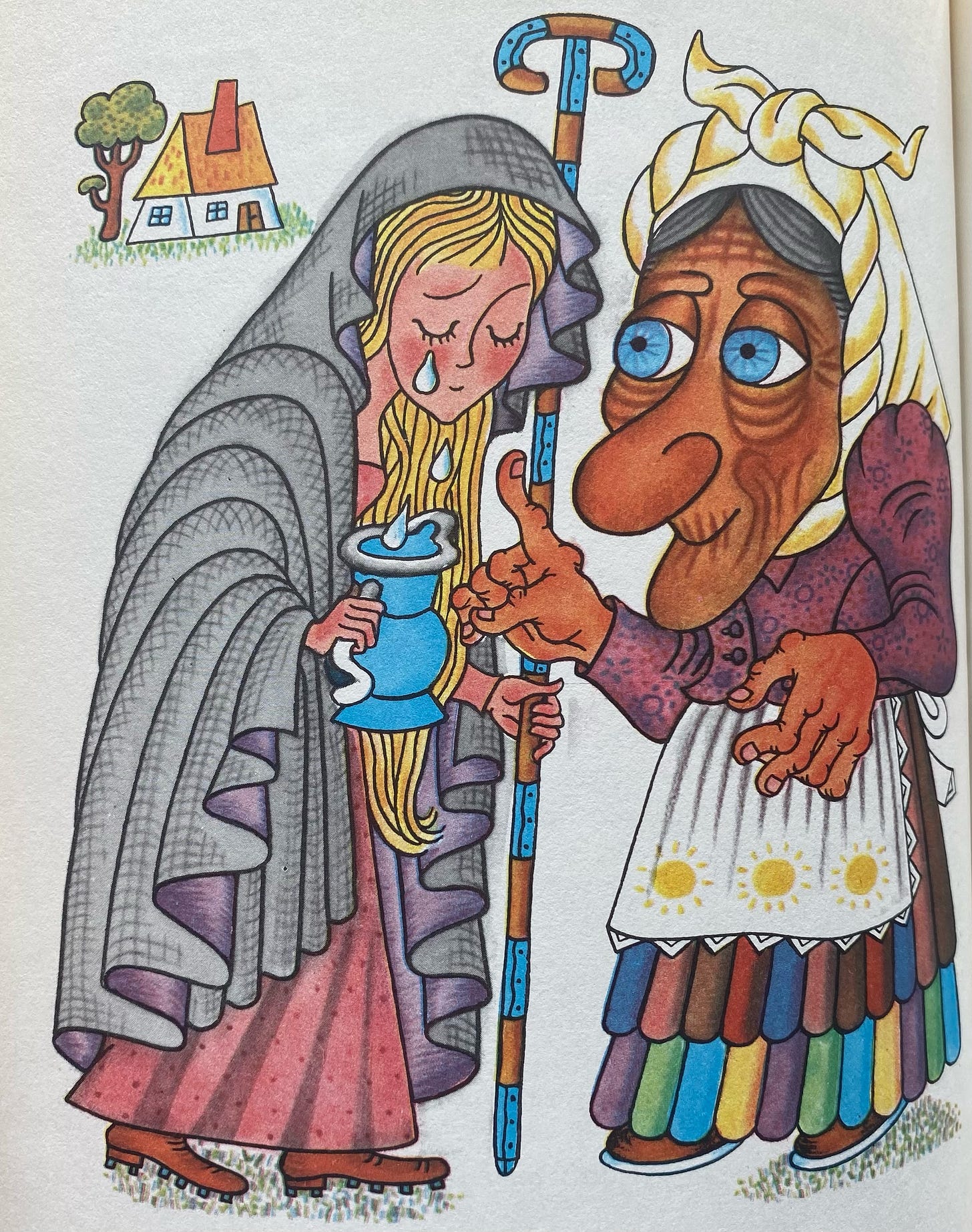

My mother reminds me she read the same fairy tale to me hundreds of times when I was a child. It was a Czech fairy tale she read in Polish from a 1972 book titled, Spiewajaca Lipka (translation: Singing Linden). She never understood why I loved it so much, she now says, but I insisted it was the only one I wanted. It pains me to admit that it was indeed about a princess trapped by an evil man, only to be saved by four other men: a prince, a fat man, a long man (not the same as tall as he stretched horizontally - I know, weird) and an eagle-eyed man. Mostly, I remember imagining the pearl crown the chosen princess wore. All the other princesses in the story wore gold ones. (The prince chose which woman he wanted to marry from a dozen different princesses - I know, gross.)

But perhaps it wasn’t the story as much as it was about the repetitive and rhythmic nature of my mother, sitting in the doorway of my childhood bedroom, the light from the hallway illuminating her tired body and her tired voice, as she repeated the same lines night after night. I knew the beginning, the middle, and the end. The characters and plot were familiar and unlike in life, there were no surprises in this story. In this fairy tale, there were no dead mothers (there are often dead mothers, Orah Mark notes) and no evil stepmothers (those are also, as I am sure you know, common). I could drift off to sleep knowing I already knew what was going to happen. Fairy tales were my mother’s lullabies.

It is nearly impossible to choose, but one of my favourite essays in Happily is The Currency of Tears. It explores how crying and tears are represented in fairy tales, referencing Pearl Tears, a mid-nineteenth century fairy tale about a girl with a dead mother (!) and an evil stepmother (!!) and stepbrother, who beat her until she cries not tears, but pearls. When I read that essay, I think of my princess’s pearl crown and my favourite pearl ring belonging to my mother I desperately want to wear but am petrified of losing the pearl. I think of another image from that same book my mother read to me every night as a child, one where a woman is forced by an evil witch to fill a jug with her tears. I think of my children’s birthdays and about holding on and letting go, about abundance and loss.

“Crying in fairy tales is like one gigantic tear, hardened into a swing for all human sadness to rise and fall. Back and forth. Back and forth. A glistening swing pulled back by all the mothers who let go, and send their children into the air. A whooshing sob made out of the place where abandonment and liberation overlap, and punctuated by a mother fading backward into the distance.”

- Sabrina Orah Mark, Happily

You can order Happily here or wherever you get your books!

Thank you for reading.