Dispatch From Berlin

On artist Käthe Kollwitz & the visual language of motherhood, war & grief

I was in Berlin last week with my partner and two young children. One of the reasons we love living in the UK (we moved from Canada nearly 11 years ago) is we can easily, and often affordably, travel to other countries nearby for just a few days. A long travel day is still a long travel day, especially with kids, but it is incredible, having grown up in the endless landscapes of Canada, far from most places, that we can be immersed in a new language, a new culture, and a new country after only a short plane or train ride. (It is less than two hours from London to Berlin by air.)

It was my first time in Berlin, and I can’t give it a fair review as all the days were dark and rainy. Unlike the other short city breaks we’ve done before, we couldn’t find our tourist rhythm in the same way we usually do. As much as I wanted to teach my children about the country’s history and what happened during the wars and until the Berlin Wall came down, I didn’t think about how heavy it would feel to explain it in an age-appropriate way repeatedly. I was often lost for words, especially in Polish, my non-dominant language but the one I try to use as much as possible with my kids, and unsure how to explain the atrocities that occurred not so long ago. (For those interested in bilingual parenting, I did switch back and forth from English to Polish when I couldn’t explain something clearly about war or the political situation at the time — perhaps a topic for another newsletter.)

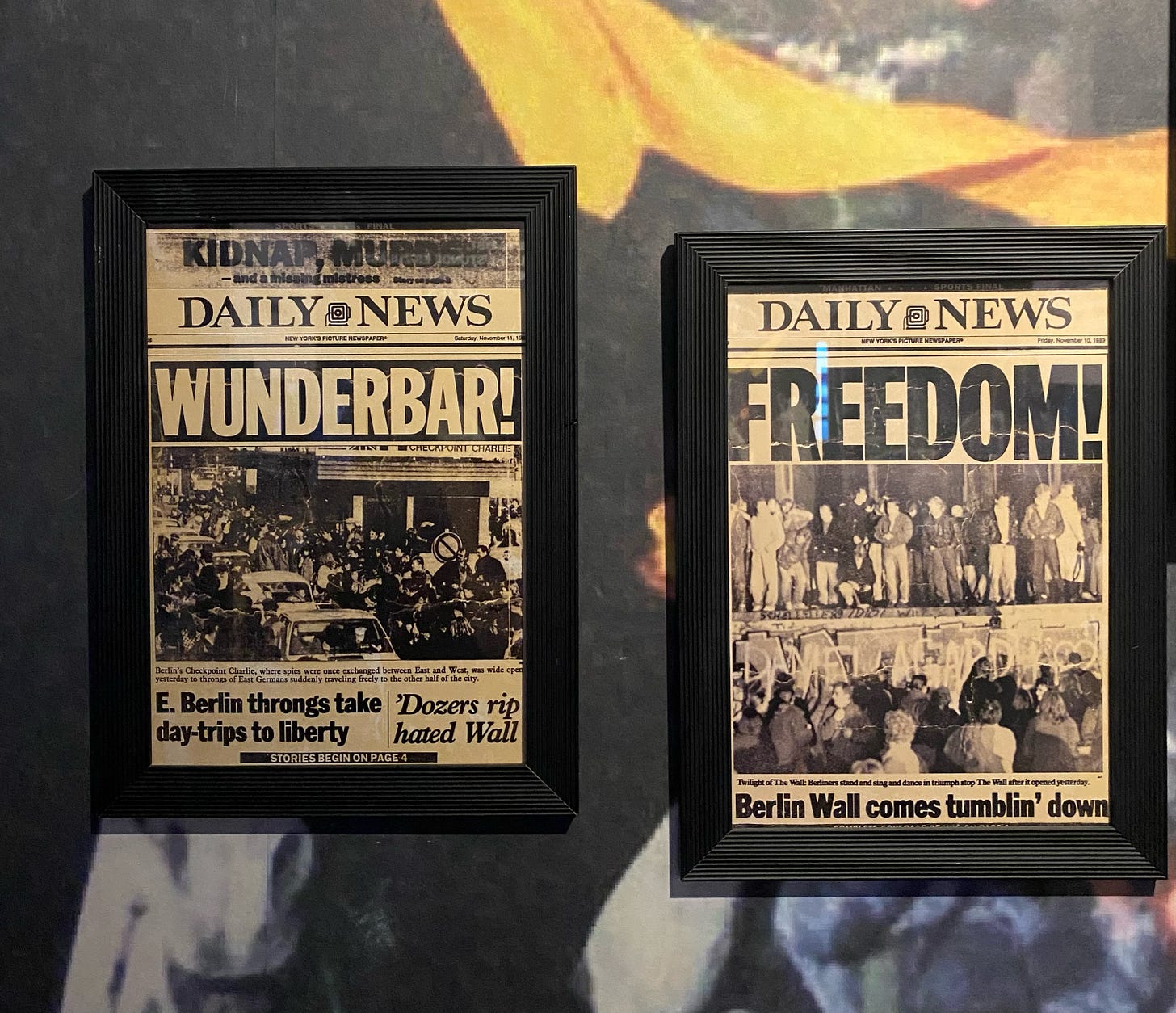

While touring the East Side Gallery, an open-air gallery of painted murals on the longest surviving section of the Berlin Wall, we went to a nearby museum dedicated to Berlin’s history from the Cold War, until the fall of the Wall in 1989. I thought it would be easier to read about the history and look at images to retell an accurate account to my kids while we were right there, in the middle of it, rather than trying to explain everything in my own words, or lack of.

And then, at the museum, my son saw an archival newspaper image of a dead child being pulled out of the river that separated East and West Berlin when the Wall was up. The image was tucked away from the main exhibit, but it was the first thing he noticed in one of the rooms. He was obviously upset, we talked at length about it, finished the tour and tried to lighten the mood for the rest of the day. But it was a stark reminder of the power of an image and forgive me for the idiom but yes, how it can be worth a thousand words when (multiple) language(s) fail to convey the message of the senseless suffering of war.

I also noticed so many images and videos of men during the exhibit: Men talking about war, men arguing with one another about war and power, men giving speeches about power, men killing each other and civilians. So, as promised on Instagram, keeping with the art-as-language narrative, and the dire need to tell the stories of what war, poverty and suffering does to women, mothers, and children, I want to share more of artist Käthe Kollwitz here.

On our third day in Berlin, we spent a rainy morning at the Käthe Kollwitz Museum and it was not nearly enough time to take it all in. Born in 1867 Kollwitz was the first woman to be elected to the Prussian Academy of Arts. Her prints, sculptures, and woodcuts are about human suffering, in all its forms, portrayed with an otherworldly beauty and empathy.

Kollwitz lived through many horrors including both world wars and the death of her younger son in WW1. She documented the suffering of the poor and starving in Berlin even before the war and the choices mothers had to make between life and death for themselves, and especially for their children. After her son’s death in 1914, Kollwitz turned to themes of war, grief and mourning in her work, even more than before. She also created many self-portraits, reflecting her own mortality and a mother’s incomprehensible grief over the loss of a child.

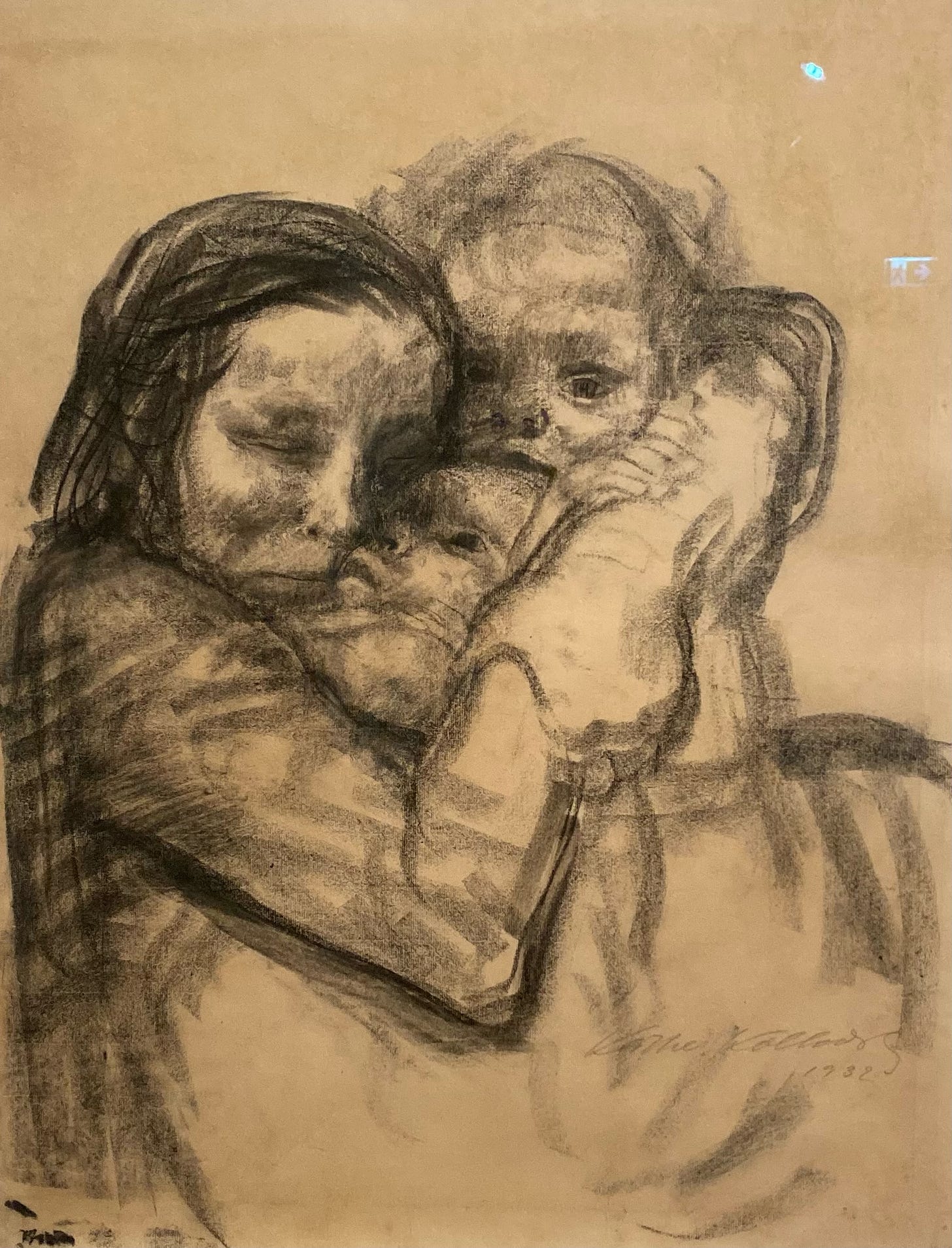

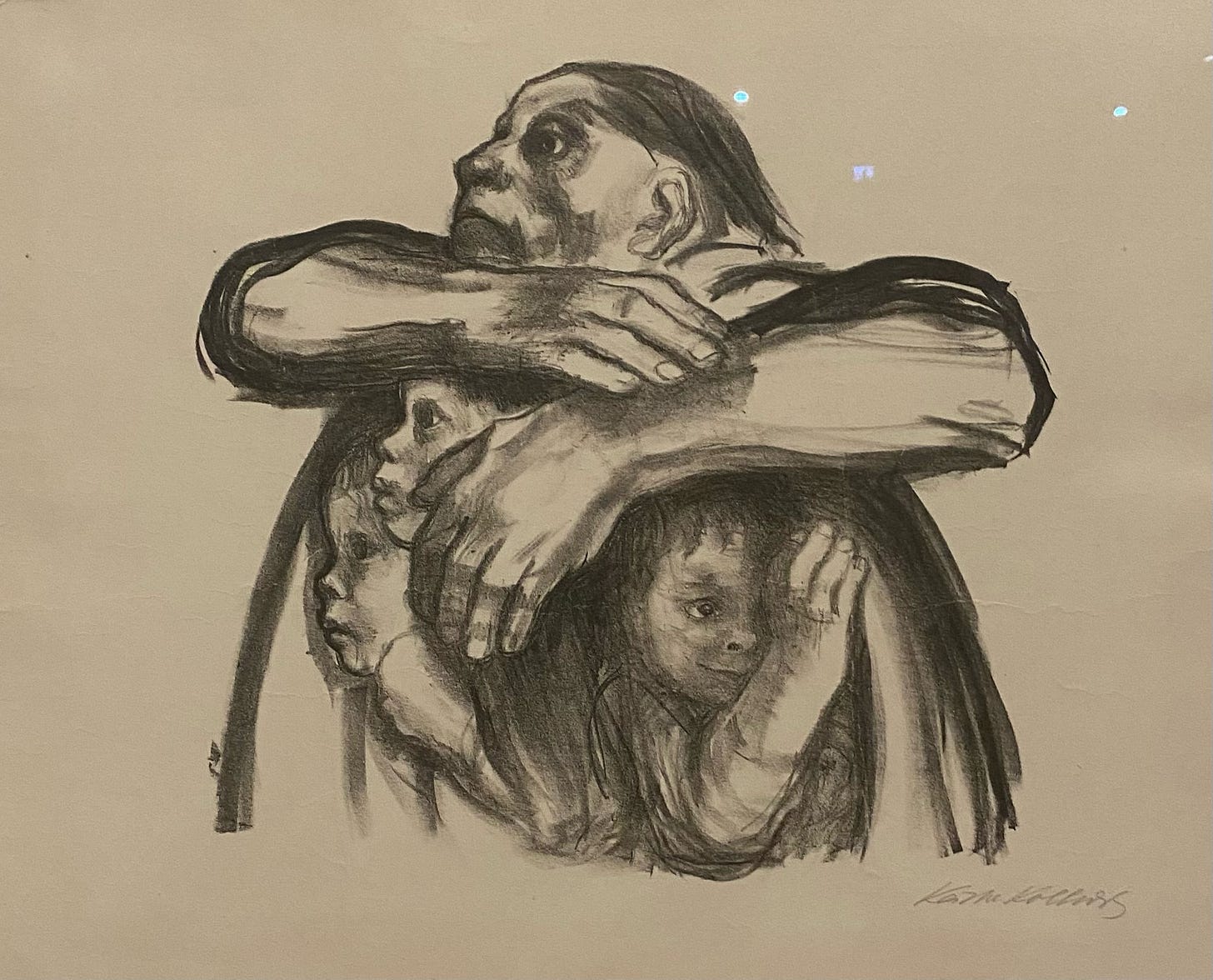

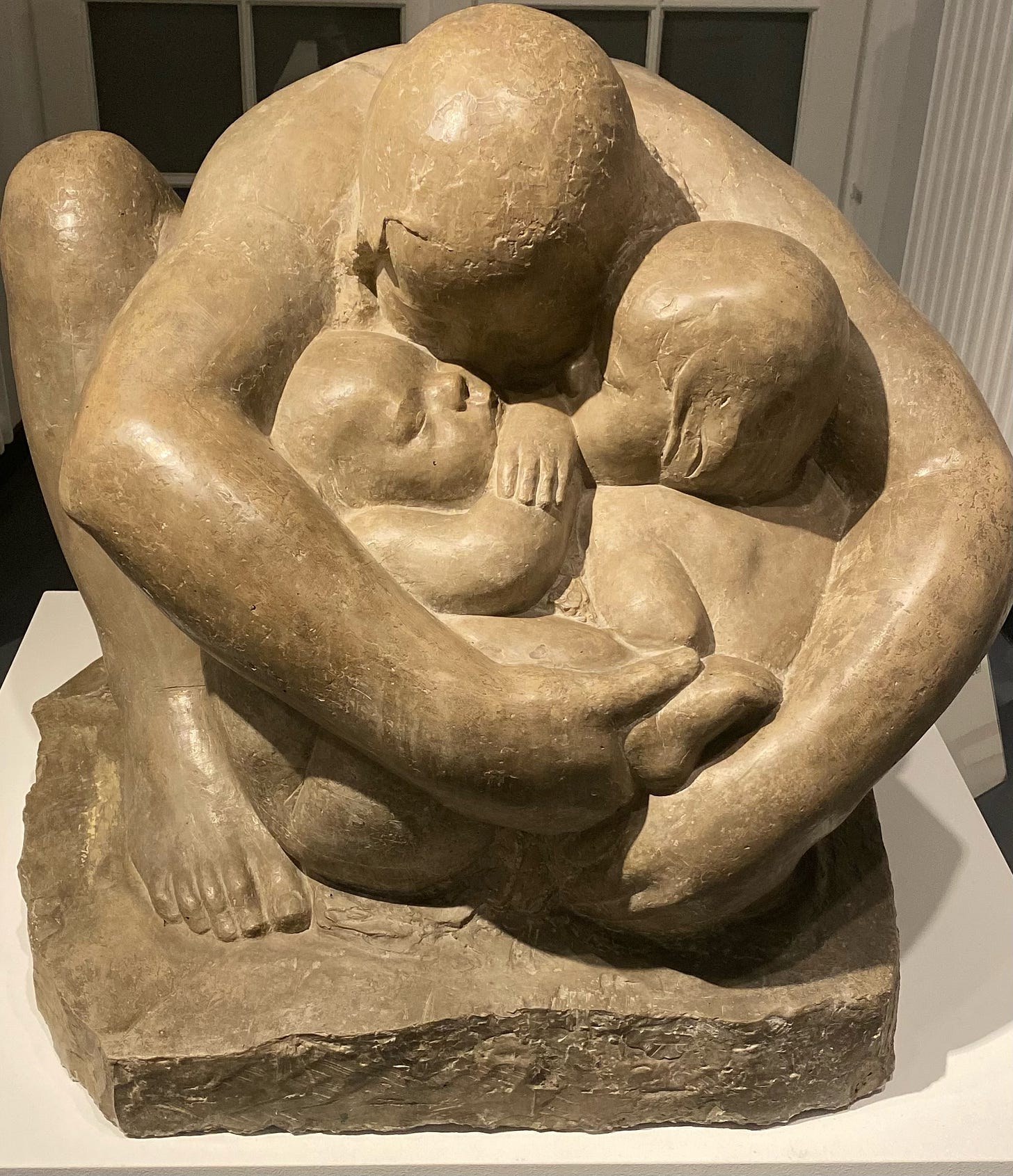

It is Kollwitz’s depiction of a mother’s hands and the theme of the embrace that affect me the most. The hands in so many of the prints are slightly oversized, either trying to envelop children and protect them from evil and suffering, or holding what seems like not only the subject’s grief but the sorrow of all the mothers in the world. Sometimes, the hands cradle new life, other times they hold death.

In the lithograph The Mothers (1919), below, one of my favourite prints and created after the death of her son, Kollwitz depicts herself and her own two sons when they were still young at the foreground of the image. It is meant to represent the limits of a mother’s protection, especially during the unpredictability of war, but also adult independence.

I could write thousands of words about what Kollwitz’s work means to me and detail every piece and how important and relevant it is still today. Mothers are constantly on the front lines of so many wars, literal but also figurative (think: war on guns, war on protecting trans children, war on reproductive rights, war on so many other unthinkable horrors), bearing the burdens of the awful choices made by others, suffering endless grief, and just trying to protect children from ignorance, danger and death.

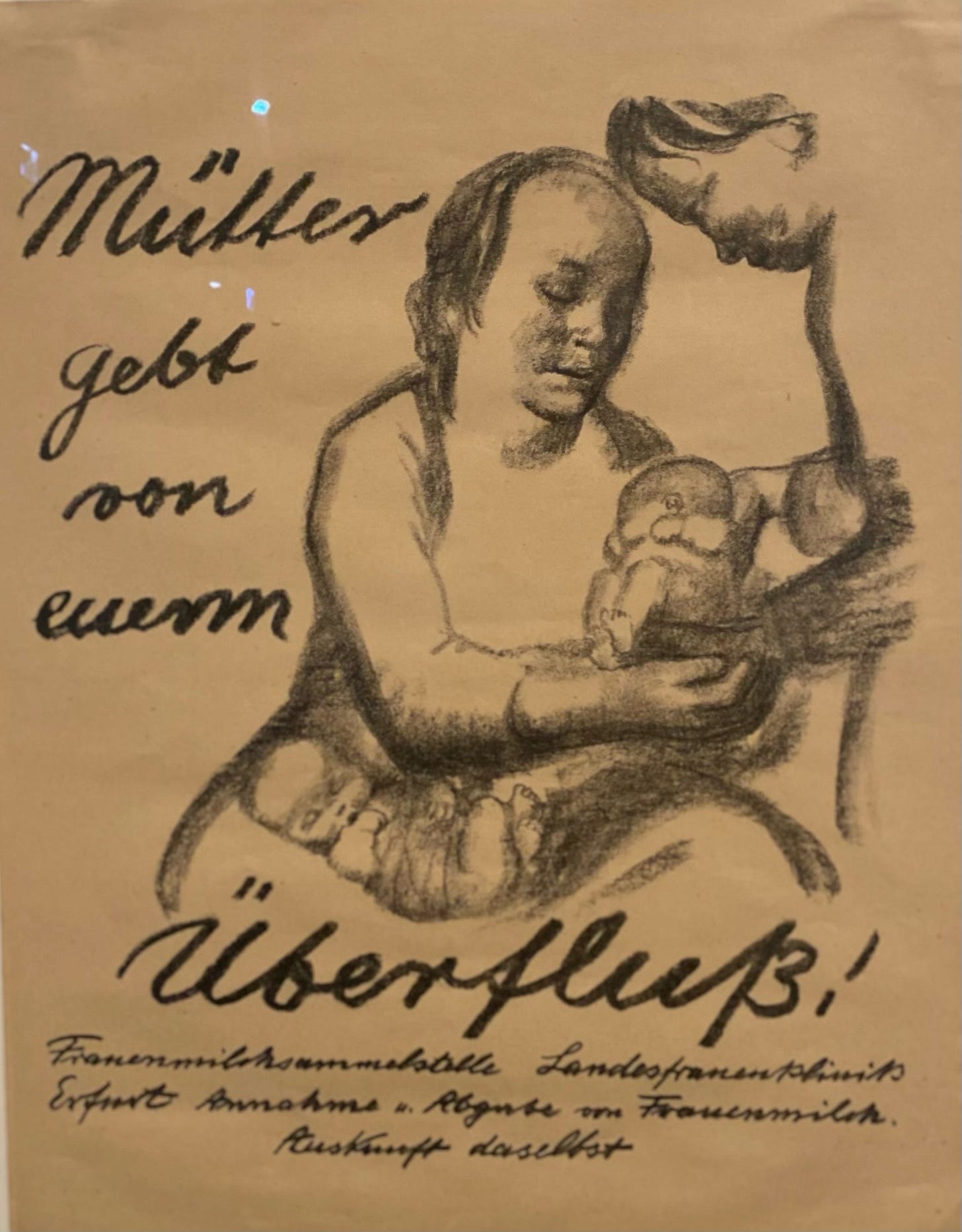

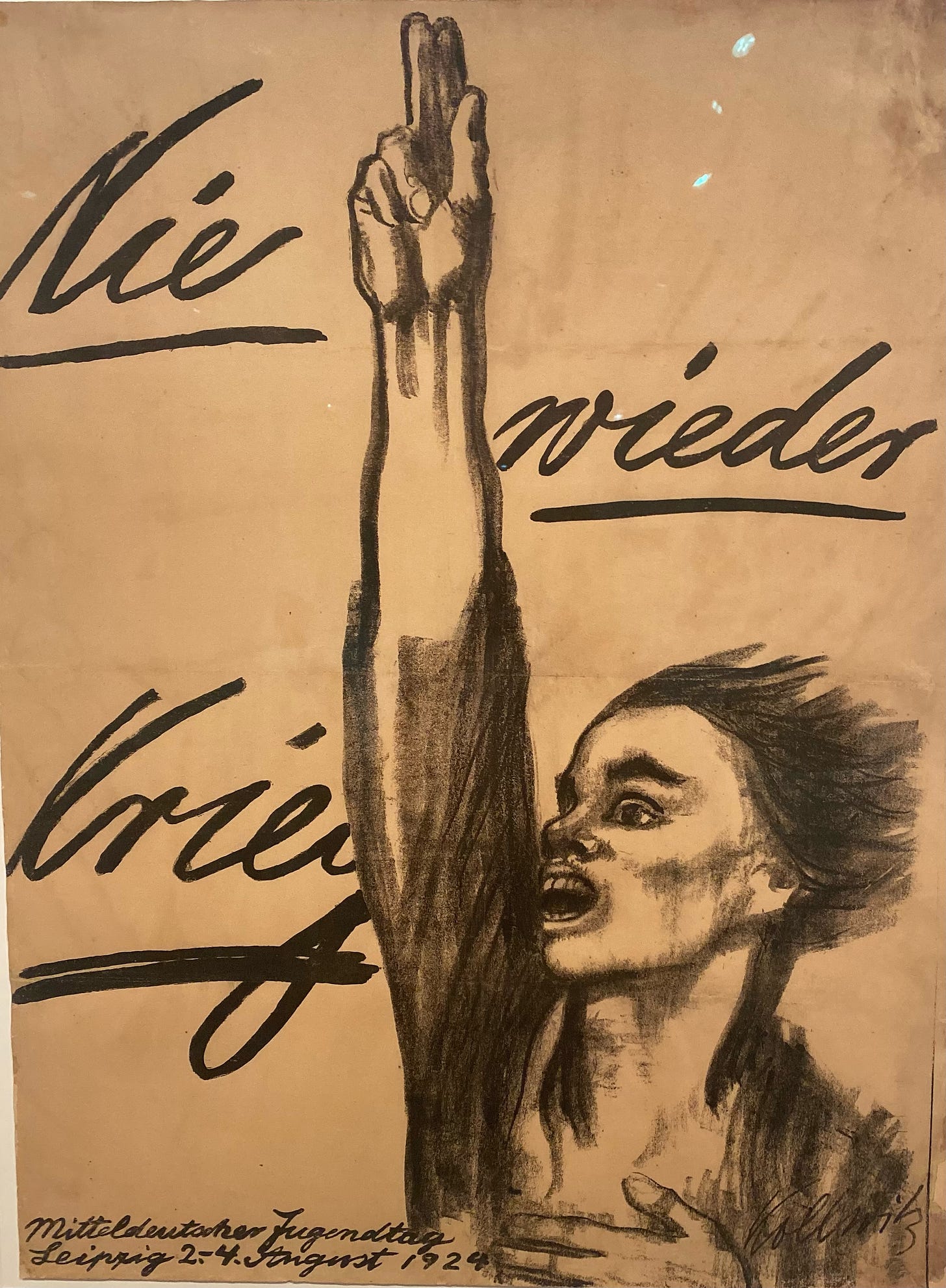

But like so many before me have said, giving up hope is not an option and amplifying voices is always the way. So I will end with the 1920s, when Kollwitz took on commissions for social causes, creating prints with slogans like Never Again War (1924) and Germany’s Children are Starving (1923). Mothers, Share Your Abundance (1926) was a poster Kollwitz created to spread the message of breast-milk donation. Germany’s first women’s milk collection point was set up in 1919 by paediatrician Marie-Elise Kayser, who asked Kollwitz to contribute the artwork.

I lied. I am going to end on Kollwitz’s 1932-1936 sculpture, Mother with Two Children. It was planned as a mother figure with one child but after the birth of Kollwitz’s granddaughters, Jördis and Jutta, the artist added a second child. The bronze is a nude mother, sitting on the floor with her arms and legs embracing two children, faces only an inch apart, three people becoming one. In Kollwitz’s mother-child work, the mothers are always as close as possible to their children, inhaling their beings and bodies, in case, and in fear of what will happen if they let go.

If you live in Berlin or have been there, I would love to hear your favourite things or parts of the city. I need to return when there is sunshine in the forecast!